What do you want?

Scripture Readings

Last week, Jesus addressed that question to James and John who wanted places of honor in God’s kingdom. Today, he addresses it to a blind man…and to us.

Last Tuesday, I was headed to lunch at a local diner called Rick’s. I parked in the lot beside the place. From there, you have to walk around to the front of the building to get inside. As I did, I noticed a man sitting at the corner of the building under a large shrub. He was wearing ill-fitting pants and shirt, wrinkled and dirty, his skin was weathered and darkly tanned, and his hair stuck out in tangles all over his head. As I passed by him, he said something. I don’t know what it was, or even if it was addressed to me. I do know that I didn’t stop to find out. I do know that I walked a little faster toward the front door. And, as I walked along, I felt ashamed of myself.

I’m a big guy. I weigh around two hundred pounds. When I was younger, I stood just shy of six feet tall. I work out. I lift weights. And yet, I was afraid of that man. Even now, when I ask myself what I was afraid of, my answers all seem unsatisfactory. He was very likely schizophrenic. I saw him later on singing and talking loudly to himself. Yet, he was probably not much of a danger to himself or anyone else—even me. Especially me. He looked dirty. He probably smelled bad. Would that have hurt me? Probably not. Those were not the things I was afraid of—the things I avoided—the things that made me feel ashamed. What scared me was his need. His need was real, palpable, and unavoidable—although I managed to avoid it. I felt inadequate to even question his need, let alone satisfy it. It scared me because, little though he was, his need was so enormous. It dwarfed me, made me feel impotent.

What should we do in situations like that? There are so many so-called “right” answers. We can speculate on whose fault it is that the social safety net of family, community, and government lies in tatters. We can lay the blame at the feet of any one of those institutions…and we’d be right. We can criticize the inadequacies of those whose job it is to care for those who can’t adequately care for themselves. We can bemoan the fact that, for even one of these mentally challenged people, or for just one of these folks addicted to drugs and alcohol, or for only one of these people so beaten up and beaten down by life that they’ve no longer got the energy or will to take care of themselves, the treatment is so demanding that no one person could possibly address it. And yet, our cities, our nation, our world is filled to overflowing with these people. It’s true. One person could not possibly confront all that need. That’s what we tell ourselves. That’s what I tell myself. Yet, I am ashamed.

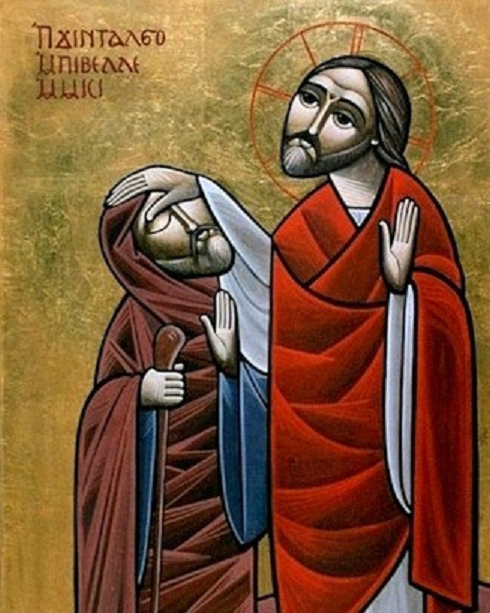

My sin—and, yes, it is a sin—was not asking a simple question. It’s the question Jesus asked James and John last week and asked the blind man today: “What do you want me to do for you?” There it is. There’s the question. It may not at first seem like it, but Jesus’s response to the disciples who asked favors from him in last week’s gospel and the blind man in this week’s gospel was the same. Last week, where James and John asked for places of honor, Jesus opened their eyes to the cost of their request: to drink of the cup he would drink and to be baptized with the baptism he would undergo. This week, in response to his request, Jesus restored Bartimæus’s sight. At least for me, for now, my answer to that question will be the same as the one Bartimæus gave: “Master, I want to see.” But when we ask Jesus to restore our sight, what are we asking for?

First of all, we’re asking to see the world as God sees it, that is, to be able to recognize in every person, no matter how physically, socially, or morally repulsive they may be, the image and likeness of God. That, too, is very often a cup we’d rather not drink from and a baptism we’d rather not undergo.

And then, we’re asking to be able to see what it is we’re able to do to alleviate some of the human misery we see around us. I’m convinced that God recognizes our limitations. Jesus was sad when that rich young man walked away from him because he was afraid to give up his wealth. But Jesus did not condemn him for it. He acknowledged how difficult it is—harder than for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle. God never asks us for more than we’re able to do. He doesn’t expect us to give away all that we possess. God knows as well as we do that the need is so great that even that would be of almost no help at all. God isn’t asking us to take the homeless into our homes and to feed and clothe them. We recognize as heroes those who do that. But even Jesus told his disciples that the poor will be with us always when they rebuked Mary Magdalen for “wasting” expensive perfume.

When Jesus asks us, “What do you want me to do for you?” and we answer, “Master, I want to see,” what should we expect Jesus to do for us? He wants us to see, first of all, the results of the good that we do. Although we say, truly, that no good deed goes unpunished, we also need to see that no good deed we do—however small—fails to help. Our cumulative care and concern as Christian people at least help keep human misery from getting any worse than it already is. But, most importantly, Jesus answers our request by letting us see that, whatever good we do, however great that may be, it will never be enough. That keeps us from falling into self-satisfaction and complacency. It keeps us hurting for those in need, sensitive to those around us, cognizant of the image of Christ in those who suffer, and even willing just to do the next right thing, to take the next positive step, to push ourselves just a bit farther out of our comfort zone.

I said at the beginning of this homily that I felt ashamed of walking away from that poor man and the uncomfortable situation I found myself in. I misspoke. Remember that the difference between shame and guilt is that guilt says, “I did wrong,” while shame says, “I am wrong.” It was not shame I was feeling, because, no matter what I do or don’t do, I’m not a bad person and God doesn’t make junk. I felt guilty—not because of something I did, but because I didn’t feel like I could do any more. Shame is a self-destructive emotion, while guilt—though uncomfortable—is a great motivator. In effect, my guilty feelings were Jesus’s answer to my prayer, “Master, I want to see.” He let me see. Now, the rest is up to me.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.