When’s a Marriage Not a Marriage?

Scripture Readings

Without a doubt, today’s passage from the Gospel of Saint Mark is one of the most difficult for people to deal with—Christians and non-Christians alike. Even today, the churches dance around the issue of divorce and remarriage with positions ranging from prohibiting it outright to allowing it for any reason. Don’t think that I’m going to settle this controversy once and for all with this homily. I’m not that good. What I’ll try to do is give you some of the background of this passage and some of the principles involved. That way, at least you’ll come away with a slightly clearer understanding of the issues.

From ancient times all the way through the renaissance, people—even Christians—had no clear idea what marriage was. The Catholic Church didn’t define marriage as a sacrament until the thirteenth century and didn’t enforce its rules on marriage until the sixteenth century in reaction to the Protestant Reformation. Some ancient cultures acknowledged women’s rights, others didn’t. Roman women could own land, write their own wills, appear in court, and sue for divorce. But for the Jewish people and many other cultures in Jesus’s time, women were considered to be property and had no rights beyond what their fathers or husbands allowed. Marriage was basically a contract for purchase and ownership of goods and so only men could divorce. Even for them, the nature of divorce was a hot topic.

Among the Jewish scholars of the first century, a debate was raging between two schools of thought. The school of Shammai taught that a man could only divorce his wife for adultery while the school of Hillel taught that he could give his wife a writ of divorce for almost any reason. Both schools based their claims on the same passage from the Book of Deuteronomy [24:1-4] that stated, “When a man, after marrying a woman,…is later displeased with her because he finds in her something indecent, and therefore he writes out a bill of divorce and hands it to her, thus dismissing her from his house: if on leaving his house, she goes and becomes the wife of another man,…then her former husband, who dismissed her, may not take her again as his wife…” This is the passage the Pharisees referred to in today’s gospel when Jesus asked them what Moses said.

The key to the differences in interpretation between the two schools of thought lies in the words “something indecent.” Shammai taught that it meant only adultery, whereas Hillel included anything that displeased the husband, even if his current wife was not as beautiful as another woman. The gospels also reflect this controversy. Mark, who wrote for non-Jewish Christians, makes no exceptions. Matthew, who wrote for Jewish Christians, in a parallel passage, adds the line “lewd conduct is a separate case” [Matthew 19:9]. The Pharisees in today’s gospel reading were using this dispute to try to trip Jesus up. It appears that Jesus may have been teaching that divorce was wrong. If he claimed that publicly, he would have been contradicting the Torah. Besides, King Herod had divorced his wife and married another, so Jesus might get himself in trouble politically as well.

But Jesus skirted the issue by skipping over the passage from Deuteronomy and taking it all the way back to the Book of Genesis [2:23-24] where it is written, “[the man said,]’This one at last is bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh…’ That is why a man leaves his father and mother and clings to his wife, and the two of them become one body.” According to this, the unity of husband and wife as one body is derived from the desire of the bodies to return to an original oneness. This was a common explanation for sexual desire. We even see it in Plato’s Symposium where Aristophanes describes humankind as having been cut in half by the gods so that the halves keep trying to reunite. By appealing to this argument, Jesus short-circuits the controversy.

In his private talk with his disciples, Jesus is quoted as being more forthright. He calls divorce and remarriage adultery. At the same time, this stance contradicts our nearly universal human experience. Can we resolve this contradiction? Obviously, Jesus is appealing to an ideal of marriage. We have to ask, is every committed union of two people—even a solemnized commitment—a real marriage? What is a marriage, anyway? We have to give the Catholic Church credit for recognizing that marriage is much more than a financial arrangement or a legal fiction. It’s more than merely a license for two people to have sex with each other. It’s even more than a solution to the question of children and inheritance. People today realize that they don’t need marriage for any of those reasons. The Second Vatican Council declared that a true marriage is a consortium vitae—a community of life and love. If that community is missing, the relationship does not fulfill the basic definition of what a marriage is.

There are many reasons why two people are unable to form a lasting community of life and love. Even psychologists recognize that some people are incapable of true commitment to another. There can be unspoken differences in fundamental values and in life goals. There may be personality traits or other mental issues that make it difficult or impossible to respond appropriately to another person’s needs. There may be an inability or unwillingness to cope with the stresses of building and maintaining a life together with another person. There may be a naïve confusion between romantic feelings and the self-denial and self-sacrifice required by genuine love of another. A community of life and love—a marriage—demands many things. This is far from an exhaustive list. You can look at your own experience and find things that you discovered were critical to maintain a loving relationship.

People don’t just “fall out of love.” They discover—sometimes after many years of frustration—that one or more of these critical elements is missing, either in their partner, or in themselves. These discoveries—these factors—are nothing new, unless some trauma happens that results in severe personality changes, like debilitating injury or illness. When relationships change or end because of a pre-existing condition, it’s not accurate to characterize this as a divorce, strictly speaking. It’s not a new decision, but rather a recognition that, despite good will and effort, the relationship just could never work. The Catholic Church recognizes these failed relationships with what it calls an “annulment,” that is, a recognition that there was some defect in the couple’s commitment to one another that made a lasting community of life and love impossible.

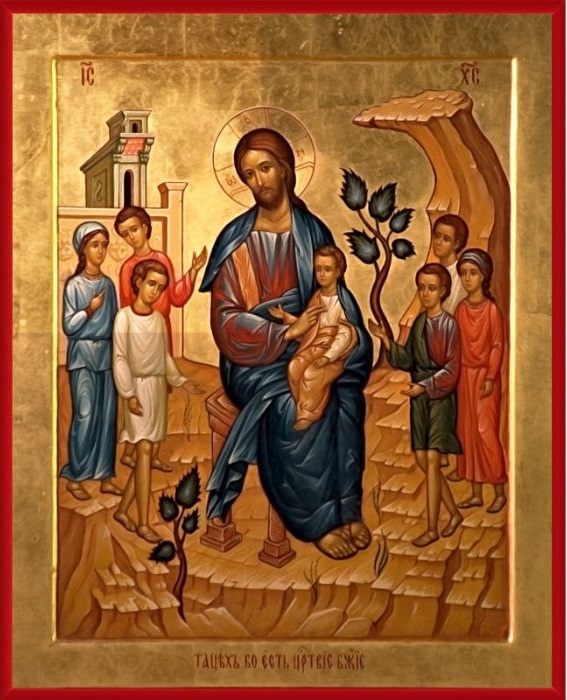

The loving gift of self of each partner in a marriage to the other creates a lasting, permanent bond. It’s that self-sacrifice that Saint Paul is talking about in his letter to the Ephesians [5:31-32] when he writes, “’For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and shall cling to his wife and the two shall be made into one.’ This is a great foreshadowing; I mean that it refers to Christ and the Church.” It’s Christ’s offering of himself on the cross and his gift of the Holy Spirit to us that creates the Church as his body alive and acting in history. That’s an inseparable bond. It’s that same bond between partners in a genuine marriage that creates a sign—a sacrament—of the love of Christ for his body the Church. Sacraments are signs of Christ’s love. They may be celebrated and actualized within the church’s structure, but God’s grace is not dependent on it. We can be forgiven without formal absolution. We can be united with Christ without consuming consecrated bread and wine. Our relationships can be signs of Christ’s love for his body the Church without formal recognition. The grace of God is boundless and available to us all, if only we can receive it with the willingness and trust of a little child.