Jesus Was a Socialist

Scripture Readings

Be warned—my comments today will be political and for a very good reason. Jesus’s comments were political. Let’s look at the gospel reading. Luke changes the lawyer’s question from the original one in Mark (what is the greatest commandment?) to “what must I do to live forever?” He does this because he was writing to a gentile audience who would not be concerned with the Jewish law. However, the discourse that follows is typical of contemporary discussions about the Law of Moses. Quoting Scripture, the Lawyer answers Jesus that what is necessary is to love God and to love one’s neighbor. Then, the lawyer gets nit-picky and asks, “Okay, but who is my neighbor?” The entire parable that follows is Jesus’s response to that question.

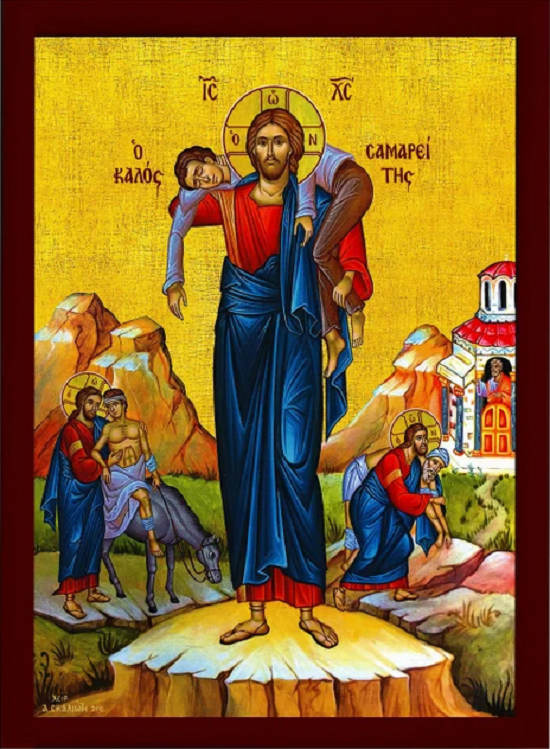

The story of the Good Samaritan focuses on a man who was mugged and left for dead. A priest and a Levite—both meticulous and orthodox followers of the law—pass the man by. Perhaps it was because they didn’t want to incur ritual impurity by touching him. The one who stopped and gave the man aid and assistance was a Samaritan, a heretic. Samaritans were triply despised by orthodox Jews of the time.

First, they were despised because they were descendants of the people of the northern Kingdom of Israel that was conquered by the Assyrians. The Kingdom of Israel revered the same Torah as the southern Kingdom of Judah, but they worshiped Yahweh in temples located in various places around Israel like Shechem, Hazor, Shiloh, Bethel, and Mount Gerizim, rather than in the temple in Jerusalem. The faithful of Judah considered their worship to be heretical.

Second, they were despised because they were not purebred Hebrews. When the Assyrians conquered a people, they assured subjugation by not only deporting the elite of that nation to Assyria, but also spreading them far and wide to all the various conquered territories under their control. Likewise, they settled their elites and the elites from other conquered territories there and put those people in positions of authority. That effectively eliminated the previous secular and religious governments. Of course, these people intermarried with the native population, diluting their bloodlines. To the Jewish people of the south, the Samaritans were considered to be of mixed race.

Finally, they were despised because the Assyrian resettlement program took away the elite classes, essentially leaving behind only the farmers and herders—the local hicks. What upper-class people from the north were able to flee to the south, and the upper classes already there despised the country bumpkins that were left behind in Samaria. In effect, the Samaritans were the victims of discrimination based on race, creed, ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic factors, but Jesus chose to make one of these people the hero of his parable.

Now, let’s get somewhat more political. Jesus doesn’t tell us anything about the injured man, but he tells us a great deal about those who “came upon” him. Two of the three passers-by did not consider the injured man worthy of their help. He didn’t meet their criteria. I just saw the movie, “Mr. Malcom’s List.” In it, Mr. Malcom, a very eligible bachelor in search of a wife, had a list of criteria that his future spouse would have to meet for him to consider her.

So, let me ask, what’s your criteria that someone must meet to be worthy of your help? A certain race? A certain creed? A certain ethnicity? A certain language? A certain citizenship? A certain socioeconomic class? A certain type of employment? A certain lifestyle? A certain intellectual capacity? Free of certain diseases? Dresses a certain way? Smells a certain way? Has a certain kind of self-restraint? Need I go on? In short, what qualifies someone to be your neighbor? Or, on a more fundamental level, what qualifications does a person need to possess for you to consider her or him to be a human being and worthy of respect, not just in theory, but in practice?

Now indulge me because I’m going to get even more political. We all walk by the needy. I do it. We can’t deny that we do it. Are we like the priest and the Levite who’ve excluded these people from our care and concern? I say, no. We all recognize these people as our neighbors, and it hurts us to feign ignorance and walk on by. But we must. Spirituality is the art of the possible. We’re not bad people because we recognize that a problem—even with just one of Christ’s sisters or brothers—is beyond us. We know that handing someone a fistful of spare change does no real good. However, we also have a collective responsibility. Even though as individuals we’re not able to alleviate others’ suffering, we’re called by Christ himself to do so not only as a Church, but as a society of fellow human beings.

There is an attitude all too prevalent in our world that is not only anti-Christian or anti-religious, it’s inhuman. That’s the attitude that says, “This is mine. I worked for it. I deserve it. I can do whatever I want with it.” If anything is a sin, I think that qualifies because it’s a deliberate and self-centered denial of reality in two directions. On one hand, it’s a denial of our interdependence. It’s a refusal to acknowledge that who we are and where we are is entirely dependent on the work and sacrifice of others, known and unknown. Unless we acknowledge our indebtedness to them and to the grace of God, true gratitude is impossible. There is not, and never will be a self-made woman or man.

The flip side of that attitude is the gross denial of responsibility. Ultimately, we own nothing, and that’s exactly what we’ll take with us into eternity. We’re just custodians, and all we have has merely been loaned to us temporarily. So, what do we think of the condition of our social safety net? Does our neighbor have to meet certain criteria to be worthy of assistance, or is merely being a hurting human being sufficient? Did the Samaritan ask the man whether he was employed, or spoke Hebrew, or a citizen, or if he was on drugs before he helped him? What about us? Can providing help ever be a waste of money? Do we resent the government taking away what belongs to us in taxes, or are we grateful to be able to contribute something to the common good? Do we boast that our taxes are lower than other countries whose citizen neighbors are not hungry, or homeless, or without medical care?

It’s easy to admire the selfless Samaritan and pity the priest and Levite in this most famous of all parables. Yet, do we, in the same breath, complain that the high cost of living “hits us where it hurts,” that is, in our purses, when we should be hit where it hurts for every hungry child, every homeless woman, man, and child, and every destitute sister and brother who suffers or dies from emotional or physical illness unnecessarily?

Yes, Jesus was a socialist who showed us our responsibility to our neighbor. And, if we’re not, then how can we call ourselves his followers?

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.