The Root of All Evil

Scripture Readings

Let me ask you a question. Do you suppose that, with all the resources on this planet and all the resourcefulness of humankind, there might be enough to feed, clothe, and shelter the entire population of the world? After all, the current global population is a hair shy of eight billion people. It seems as though there should be enough, don’t you think? And we’re always producing more. If what we have and what we’re capable of creating is sufficient to support life on this planet, why are there so many lacking the basic necessities of life? Why the inequalities? I once heard a missionary priest claim—and I don’t personally agree with him—that, if you have two shirts in your closet, there’s someone on the planet going shirtless. The statement may be extreme, but the message isn’t.

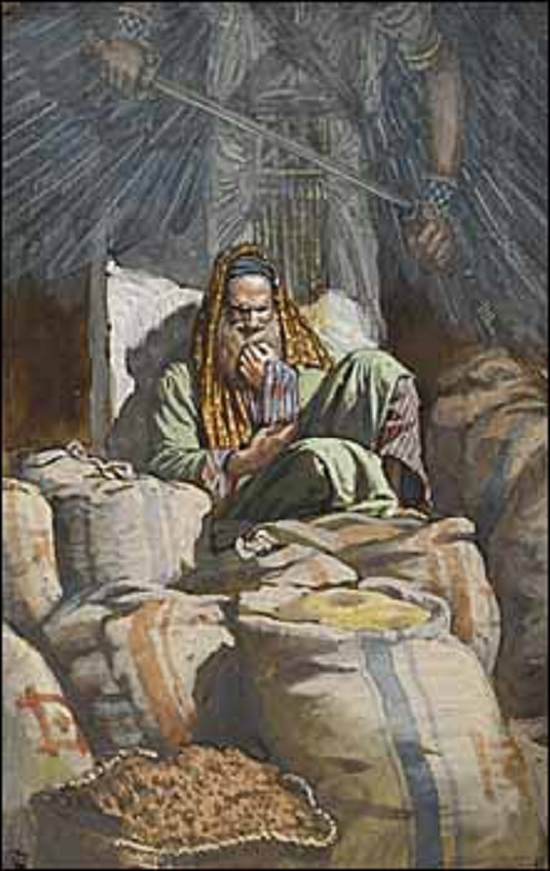

Let’s not get bogged down in economic “isms:” capitalism, communism, socialism. There is no perfect economic system. Jesus didn’t teach anything about a system. What he taught was metanoia—a personal change of mind and heart, a change of attitude. Look at today’s gospel from Saint Luke. It’s a true parable. Nobody has tried to turn it into an allegory or give the story a moral. The story simply stands on its own, and we’re invited to ponder it. Obviously, its theme is possessions—that is, our attitude toward the resources of this world. Jesus never condemned the ownership of material things. Despite the vows of poverty that some people take in dedicated religious communities, Jesus never demanded renunciation of material goods. He never suggested that material things were evil. Neither did Saint Paul. He didn’t say that money was the root of all evil, he wrote that love of money is the root of all evil [1 Timothy 6:10]. There’s a vast difference between possessions and possessiveness.

There’s another name for possessiveness, and that’s greed. It’s even one of the seven so-called “deadly” sins. In our first reading this morning, the Preacher, Qoheleth, calls greed vanity—in other words, a futile pursuit. In today’s second reading, Saint Paul goes a step further. He calls it idolatry. Let’s look at human nature to see why.

According to French Sociologist Marcel Mauss, human beings’ relationship to material goods is based in magical thinking. Possessions endow the possessor with a kind of status and power he calls mana. He defines mana as “the force in the thing.” We, too, believe in mana. When we have people over to a dinner party, mana shifts. Our guests now owe us a dinner in return. They are in our debt—a debt of mana—until the debt is repaid. If they fail to repay the debt of mana, they lose status. We also see our belief in mana in the way society treats the wealthy, giving them deference, which provides them with status and power. Their possessions don’t make them more powerful; our envy and deference do—in the hope that we’ll share in some of their mana for ourselves.

That craving for mana—for status and power—for a state of self-reliance is the driving force behind all greed. And it’s in the pursuit of self-reliance that we find the idolatry. We crave independence—independence from need, independence from acquisition, independence from responsibility, independence from accountability, independence from reliance on any one or any thing, including God. Therein we find the idolatry. Therein we find the arrogance. And that’s not all…therein we find the vanity, and as the Buddha saw so clearly, therein we find the suffering.

Since our possessions themselves are not the cause of our troubles, but our attitudes towards them are, getting rid of stuff will not alleviate our malaise or preserve us from spending our lives chasing after ephemera. As always, for followers of Jesus, all we really need is a change of heart. But it’s a big one. It requires a shift of attitude from the one that says, “I’m responsible for my own security and happiness,” to one that embraces the radical statement, “In all things, I am a debtor.”

What do I mean by that? I mean simply that everything is a gift. Everything I have and everything I am I owe solely to the grace of God. Nothing, in the end, is mine. Like our food, our possessions are given to us for a season to support and sustain our lives but ultimately, they must pass from us. Acknowledging that, in all things, I am a debtor means I have no mana—no status, authority, or power—that has not been loaned to me, and for which I am responsible to others and, especially, to God. That’s what we mean by the word humility. It’s a recognition of our radical dependence.

Let me end by saying this: without acknowledging our indebtedness—regardless of our apparent wealth—without humility, there can be no genuine gratitude, no thanksgiving, no eucharist. Therefore, if you want a measure of your humility, you need only ask yourself, “How grateful am I?” For, wherever you struggle to find gratitude, in whatever area of your life you find anything unacceptable, that’s where you’ll find your lack of humility, your arrogance, and, at the end of the day, your greed.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.