Work without Prayer Destroys

Scripture Readings

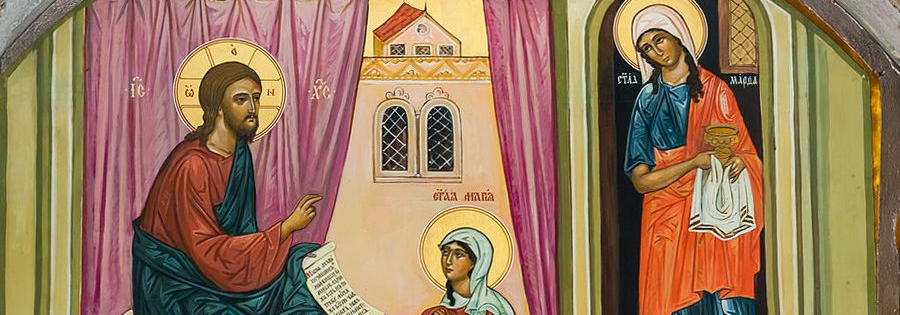

From the earliest days of our Christian community, the story of Martha and Mary has been used to illustrate the differences between the active and contemplative lifestyles. Although related, these two approaches seem to be polar opposites, each working against the other. Even Jesus’s admonition to Martha that “Mary has chosen the better part” reinforces that idea. Still, spiritual giants like Saint Benedict and Saint Ignatius of Loyola saw that the two must work together to form a healthy spiritual life. Benedict’s motto for his monks was, “Ora et Labora,” meaning “Pray and Work.” Ignatius of Loyola taught his Jesuit brothers with the saying, “Pray as if everything depended on God; work as though everything depended on you.”

Of course, we, who see God’s fingerprints all over our universe understand our utter dependence on God. Even many of those who don’t believe in the God and Father of Our Lord, Jesus Christ acknowledge their dependence on a Power greater than themselves and the necessity of maintaining a conscious contact with that Power, however it’s understood. The prayers of humanity rise up always and everywhere from our little planet. Most of these are prayers of petition—God grant me this or God grant me that—or they’re prayers to effect change—God, please do this or God, please don’t do that.

In today’s gospel, Mary’s prayer that Jesus held up as an example was nothing like that. It consisted of Mary sitting beside Jesus at his feet and listening to him. She simply sat in his presence and listened. That’s all. Today, we call that contemplative prayer or listening prayer. Like those of us who practice contemplative prayer today, I’m certain that, as Jesus spoke, Mary’s mind sometimes wandered. And, like us, I’m sure she kept bringing her attention back to refocus on Jesus. Like the Buddhists, we set our intention to prayer, then let our random thoughts and distractions pass by us unobserved. If we’re not asking God for anything in contemplative prayer, how will that change anything, and if it won’t change anything, why do it?

Let’s look again at today’s readings. When Jesus came to Bethany, to the home of Martha and Mary and his friend, Lazarus, he didn’t come alone. During Jesus’s public ministry, we sometimes hear of him going off by himself to a deserted place to pray. The rest of the time, he traveled with an entourage—at least the twelve and the women followers who attended to their needs. So, as a result, the house in Bethany was full of people. No wonder Martha was stressed out. The rules of hospitality were unbending—hearkening back to the time of Abraham.

In the first reading today, the Scriptural author lets us in on a secret: Yahweh God has come to Abraham in the form of three strangers. Many Christian authors see in those three a prefiguring of the Trinity but, of course, no such idea was entertained at the time. Some ancient commentators understood them to be angels, that is, manifestations of God’s presence. In any case, Abraham showed the men honor—this was standard hospitality for the nomadic Hebrews—but Abraham then went above and beyond. One could say that he went overboard, preparing a feast for the visitors out of the best of what he had to offer. Remember that these were not his family, his friends, or even people whom he recognized. These were strangers.

His generous hospitality merited him a blessing—his wife, Sarah, would conceive and bear a son in her old age—because, unbeknownst to him, Abraham had welcomed and entertained Yahweh God. Ever since, the Semitic peoples of the Near East have welcomed strangers generously because one never knows when that stranger might be an angel or God himself.

So, you see, Martha’s work was the fulfillment of a solemn obligation. What she was doing was important. Yet, Jesus said that Mary had taken the better part. Why? I think the reason can be found in the nature of contemplative prayer itself. It does not change God; it changes the one who prays. Martha was so caught up in what she was doing, that she lost sight of the purpose of her work. That’s us without contemplative prayer. We generally know what we’re doing, and most often we know why we’re doing what we’re doing. What we generally lose sight of is whom we’re doing it for.

When we lose track of whom we’re working for, we not only turn a blind eye to divinity—we have no thought of entertaining an angel, let alone Yahweh God—but we forget about their humanity. We wind up working for profit or goods or projects to fulfill our wants and desires. These things become ends in themselves and eclipse the deeper, personal values they were meant to serve. So, to make money, we fail to pay our workers a living wage, sending them to live in their cars or on the street. To manage our tax burden, we turn the mentally ill and addicted out to fend for themselves. We cut our support of education and healthcare to the bone. To avoid the inconvenience of having to deal with strangers, we turn them away from our borders, incarcerate them, and tear their families apart. It’s a very short step from there to putting inconvenient people permanently out of our misery.

Jesus, Saint Benedict, and Saint Ignatius of Loyola all acknowledged the critical importance of contemplative prayer as the foundation and guide of all our work. With it comes the recognition of the presence of God in every person—friend or foe, family, neighbor, or stranger, regardless. With it comes generous hospitality and tender compassion. With it, our anxiety, our worry, our burdensome service has meaning, purpose, and direction. Without it, our work is less than useless. It’s destructive.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.