Selfless Eucharist

Holy (Maundy) Thursday Scripture Readings

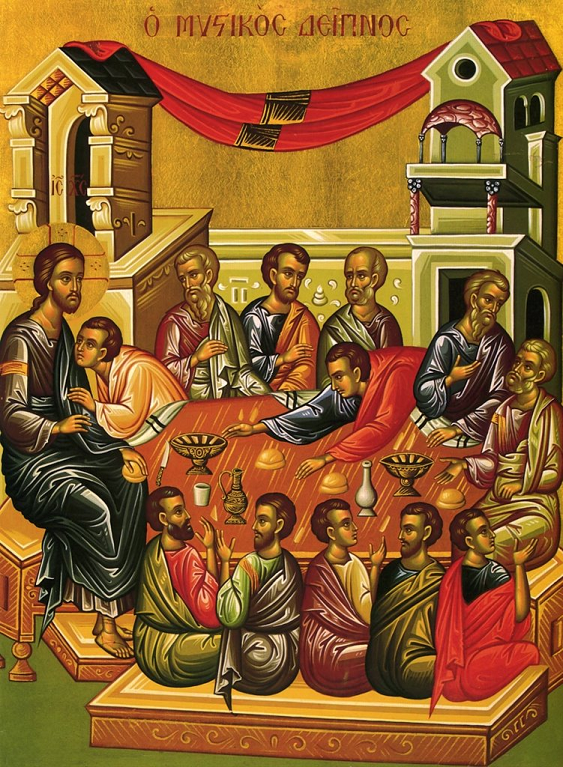

Today, the door opens not only onto the core events of our Christian faith but to the foundational structure of our lives as Christians. Belief in Jesus as the Christ—the Messiah—without the metanoia—the change of mind and heart—that faith demands is an empty charade. Our Church, in its structuring of our communal worship, uses that spotlight to teach the Christian community a critical lesson. On the first Sunday of the Passion, which we know as Palm Sunday, the Church provides us with narrations of the Last Supper, the suffering, and the death of Jesus in a three-year cycle as told by Matthew, Mark, and Luke, respectively. For them, the Passion of the Christ is intrinsically linked to the Passover meal, commemorating Israel’s passage from slavery to freedom and the passage of the angel of death over the houses of the Israelites marked with the blood of the Passover lamb, sacrificed and shared. The focus is on the unleavened bread taken, blessed, broken, and given, and on the Cup of Blessing shared among them. Eucharist is revealed as an action of thanksgiving for the gift of enduring life through union with Body and Blood of the Messiah, broken and shared.

In his typical fashion, John turns the spotlight of his gospel away from the Passover feast—the most obvious interpretation—and, without downplaying that focus, shows us a deeper and equally profound meaning. And so, today and tomorrow, Holy Thursday and Good Friday, the Church adopts the Johannine perspective exclusively. John doesn’t ignore the Bread of Life and the Cup of Eternal Salvation in the Eucharist. On the contrary, he dedicates the whole of chapter six of his gospel to it. However, he relates these occasions of the Last Supper and the Crucifixion to another reality: the thanksgiving sacrifice of service. To understand how John views the events of Christ’s Passover, we might turn to what we call the Kenotic Hymn that Paul included in his letter to the Philippians [2:5-11]. He writes, “Have among yourselves the same attitude that is also yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be grasped. Rather, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave.”

In the other gospels, we find Eucharist presented as thanksgiving for God’s saving actions as for a gift received. Here in Saint John’s Gospel, we find the same Eucharist, but this time as obligation. In John, we experience Eucharist in terms of owing a debt of gratitude that demands a response in kind. It’s clear that, for us, the Eucharist conveys the real presence of the Body of Christ. Yet, through faith and Baptism, we are the Body of Christ. The Eucharist is our recognition and celebration of who we have become. In the Eucharist, we receive who we are. And who are we? We’re those who, like Christ himself, lay aside any claims to grandeur and importance that we may have, to assume the condition of a slave—a slave to the will of the Father, a slave to the service of one another.

In both John’s Last Supper and his Crucifixion narrative, we see the same themes: surrender and sacrifice. We see a model for the metanoia from self-importance to humble service. We see the surrender and the crucifixion of the ego for the sake of others. For John, the Eucharist means offering mercy, compassion, humility, and selfless service. In this sense, Eucharist and Baptism are conjoined. Since Baptism is our union with the death and resurrection of Christ, Eucharist is the service that gives flesh and blood to the risen Body of Christ.

This reflection on the Last Supper from John’s Gospel has given me a new and different perspective on the words of Saint Paul to the Corinthians with regard to their celebration of the Eucharist. He said, “For anyone who eats and drinks without recognizing the Body of Christ eats and drinks a judgment on themselves.” [1 Corinthians 11:29]. I’ve always taken that as referring to the presence of Jesus in the consecrated bread and wine of the sacramental Eucharist. However, from John’s perspective, it can apply equally well to his presence in the poor, the needy, the homeless, the downtrodden, and the dispossessed. I would surmise that those who receive Communion and still ignore or even despise the anawim—God’s little ones—must face the same judgment for failing to recognize them as the Body of Christ and as real Eucharist. As we worship Christ present among us in our sacramental Eucharist at the conclusion of this liturgy, and as we spend with him our hour of adoration, we mustn’t forget that it doesn’t end there. Our thanksgiving—our Eucharist—summons us to go out from here to find him also in our service of one another.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.