Living the Bread of Life

Eighteenth Sunday Scripture Readings

Nothing in this world is entirely good or entirely evil. Yet, we assume that the things that catch our eye—the things that we pursue with such ardor—will be worth our efforts. And, for the most part, we try to avoid what isn’t. We assume that we would recognize evil if we were to see it. Theoretically, that would be true. The problem is that, since nothing in this world is entirely good, everything we value and everything we pursue is only partially good. Regardless of how valuable and necessary and satisfying anything may appear, everything we obtain will ultimately leave us wanting, hungering for more.

Jesus spoke to the crowds who followed him across the Sea of Galilee to the deserted place and were fed, and who then tracked him down again back to Capernaum, and he criticized them for their misplaced values. Whenever we find Jesus critiquing others—the crowds, the disciples, or the scribes and Pharisees—I think we tend to identify out. After all, we suppose, we’re not like them. But John and the other evangelists didn’t include these critical statements of his just for historical accuracy, nor to make us feel superior, saying, “Yeah. Right. You tell ‘em.” Unless we’re willing to apply Jesus’s criticisms to ourselves and our attitudes and behaviors, we run the risk of missing these vital lessons.

It’s very possible to indulge in spiritual pursuits for mundane reasons. Perhaps we contribute to charities for tax purposes, or to look good to others, or to avoid feeling guilty about not doing enough to help those in need. Or maybe we attend church because they say we have to, or to be seen, or to soothe our consciences. How about prayer and meditation? Is it just to feel more relaxed and centered, or to keep from feeling bad because we know we should be doing it, like diet and exercise? Could that be the reason why we don’t do it more often? My favorite quote on the subject is from T. S. Elliot in his play, Murder in the Cathedral, where Thomas Becket declares, “The last is the greatest treason. To do the right thing for the wrong reason.” Much as we’d like to opt out of the criticism Jesus levels at the crowds, we cannot. The good that we do is not always the greatest good. When our motives are mixed, we can’t be condemned outright for it, but we can’t be congratulated, either.

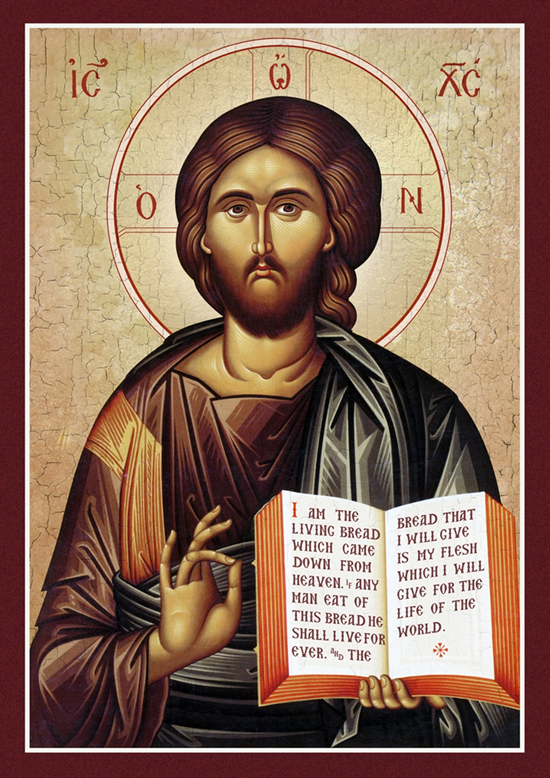

The bread of life is not a thing. It’s not mana in the wilderness. It’s not loaves and fishes. It’s not even the bread and wine of the Eucharist. The bread of life is a person with whom we enter into a personal relationship—I and thou. It is Jesus, the mediator of a new and interpersonal covenant between us—each one of us—and God, our heavenly Father and the source of all that is. As Jesus said to Philip, “Have I been with you this long and still you do not know me? Whoever has seen me has seen the Father.” [John 14:9] In fact, no human person can see the Father except in and through the eternal Word that has become flesh among us. We might even say that the Word of the Father is love.

What kind of love? It’s not ἐρος (eros), sensual love; nor is it φιλια (philia), emotional love; but it is ἀγαπη (agapē) love with the whole mind and heart and soul and strength. It’s the love we find spelled out for us in the prayer of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, “Teach us, good Lord, to serve you as you deserve; to give, and not to count the cost, to fight, and not to heed the wounds, to toil, and not to seek for rest, to labor, and not to ask for reward, except that of knowing that we are doing your will.”

I realized when I was composing this homily that if I were to ask, “What is the bread of life?” I’d be asking the wrong question. Should the question not be, “Who is the bread of life?” and, of course, the answer would have to be “the love of God manifested in Christ Jesus the Lord.” [cf. 1 John 4:9] After all, it was he himself, in the words of Saint John, who said, “I am,” that is, Yahweh, “the bread of life.” When we love as Jesus loved, through the self-giving power of the Holy Spirit, we are one with the bread of life and there remains nothing else in this world we need to satisfy us. Yet, the love that is the bread of life does not satisfy our every desire, rather it quenches them. When we’re transformed into love, what more could we want? All that remains to us is gratitude—thanksgiving for the image of Christ that we have become.

Listen to the words that Saint Paul wrote as a meditation on the bread of life. “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor present things, nor future things, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.” [Romans 8:38-39]

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.