Why Forgive?

Fourth Sunday of Lent Scripture Readings

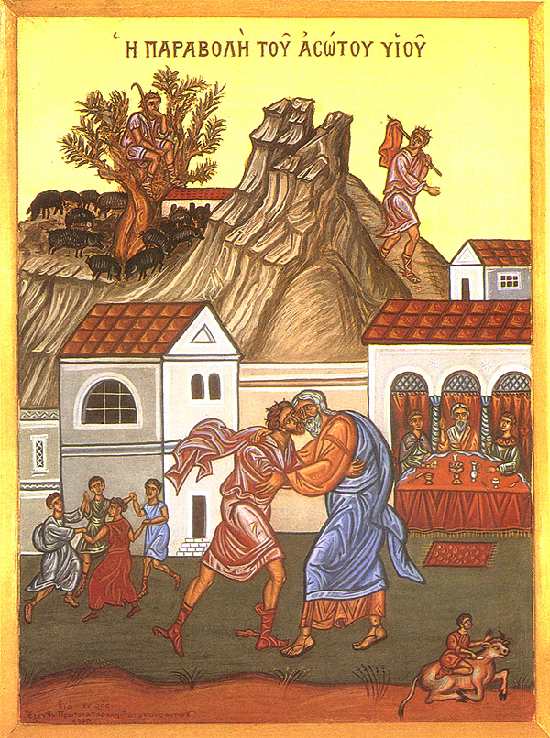

The parable in today’s gospel reading is popularly known as “The Prodigal Son,” and it’s one of the most familiar of Jesus’s parables. I think I’m allergic to what’s most familiar and the popular wisdom that derives from it. Of all the characters we meet in this story, the prodigal son is the one I’m least interested in. You see, the story’s not about him at all, and he only serves as a catalyst for the interaction between the father and his elder son. As always, Jesus’s parables are meant to teach us, his listeners, a spiritual lesson as we meditate on the drama set before us. The lessons we can draw from this story are all about forgiveness, but they’re not as obvious as one might have you believe. I’ve identified three important lessons woven into this narrative.

The first lesson regarding forgiveness centers on the father. In his generosity and, perhaps, fatherly wisdom, he gives his younger son his share of what would have been his inheritance. A wise father allows his children to make their own mistakes and, while they’re young, he safeguards them from making harmful ones. But this young son is now an adult and must make his own way without the comfort of a parental safety net. As expected, the young man squanders his wealth and falls on his face. He finally comes to his senses and realizes the value of what he had but has no longer. He returns home. The father rejoices to see him. Why? Because he knows the young man has learned a hard lesson…and survived it. Like any father, he’s relieved to see that, after all, he’s okay.

Do you think the father forgave him? I don’t think so. At least not the way we understand forgiveness. You see, the father understood that the son did nothing to him. Nothing at all. What the young man did was only to himself. And there is our first lesson in forgiveness. We need to understand that, regardless of what someone else did or didn’t do, it was never about us. It was always about them and their selfishness or greed, their fears, anger, and resentment. If we suffered harm at their hands, we need to realize that we were only collateral damage from the war going on within them. The father, with his age and wisdom, understood that and, of course, welcomed his son back into his life. At the same time, I think both of them understood that the son was now going to have to clean up his own messes. By his own choice, the son was now on his own.

The second lesson that this parable teaches is the one taught to us by the older brother. He had not yet understood the lesson that the father had learned long ago—that is, that no matter what the issue is, it’s not about him. The older boy imagined that, somehow, his younger brother’s squandering his share of the inheritance was an affront to him. He took it personally and resented his younger brother for it. There’s a cogent saying I once saw on a sign outside a church: “Righteous indignation is envy with a halo.” He was secretly angry that he wasn’t the one getting his share. So, he turned on his father and blamed him for what seemed to him to be his father’s callous indifference to him and his needs and wants, favoring his brother over him. When we look at this situation—and situations like this that we might have found ourselves in—it’s helpful to remember there’s a world of difference between giving offense and taking offense. The older brother took offence where none was given.

As I said, the older brother had not yet learned the lesson that whatever anybody else does is not about me. This fellow made it all about himself and thereby played the victim. “Oh, poor me! Look at what I didn’t get to do.” Isn’t that exactly what we do when we take things personally? Yet when someone offends us, do we really think that they’re giving us any thought at all? If they were, do you think they’d continue offending or trying to harm us? When we find it hard to forgive someone for what they supposedly did to us, aren’t we actually indulging in self-pity like the older son? “Oh, poor me. I don’t deserve this treatment.”

Ask yourself, who was actually hurt in this story, and who was responsible for it? The father got to restore and probably improve his relationship with his younger son. The prodigal boy learned valuable lessons about self-control, self-denial, humility, and the value of close relationships. The only character left out in the cold was the older son, who sat alone outside the feast, feeling sorry for himself. That’s the price we pay for holding on to resentments. That’s what we’re left with when we refuse to forgive. Forgiveness is never the condoning of anything anybody else has done. Like the younger son, the price they pay for wrongdoing is on their own heads. Forgiveness has nothing to do with that. Resentment is taking poison and expecting the other person to die. Forgiveness is letting ourselves off the hook and setting ourselves free from the illusion that what was done had anything to do with us.

The third and final lesson I took from today’s parable is about the spiritual cost of unforgiveness. In the story of the unforgiving servant whose master forgave his large debts but who refused to forgive the small debt owed to him, when the master heard about it, he “handed him over to the torturers until he should pay back the entire debt.” Jesus ends that parable with the admonition: “So will my heavenly father do to you unless you forgive your brother from the heart.” [Matthew 18:34-35] Do you really think that our God will hand us over to torturers if we don’t forgive those who owe us an apology? It’s hardly necessary. As we’ve just seen in the case of the elder son, unforgiveness is actually rooted in selfishness and based on an inflated opinion of ourselves. It leaves no room for the saving principles of acceptance, surrender, and gratitude. Also, unforgiveness carries with it its own punishment because when we’re pouting and feeling sorry for ourselves because of the injustice done to us, we isolate. Unforgiveness causes us to shut other people out, not just the imagined cause of our misery, but everyone else as well, including our God. There’s no room for God in a resentful heart.

If we want to see the torturer we’d be handed over to for our unforgiveness, we’d have only to look in the mirror. In the end, forgiveness of others is a gift we give to ourselves.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox