Step 4: Taking Inventory

We’ll begin by looking at what Step 4 actually says, but, before we proceed to examine it, we’re going to need to get rid of some serious misunderstandings arising from poor explanations of what’s involved, and the cultural fallacies that those misunderstandings have created. Here’s the fourth step:

“Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.” Let’s talk about this “moral inventory.” For Catholics and other Christians with a tradition of confessing sins, that process begins with a so-called “examination of conscience.” The “moral inventory” that we’ll be looking at in this step functions very differently from that.

To make sure that we understand the differences, we need first to see what is meant by a traditional “examination of conscience.”

The examination of conscience begins with being alone with ourselves and engaging in a mental review. A review of what? We try to think of everything we did wrong since our last examination of conscience. Generally, people are taught that the things we’ve done wrong are “sins.” In other words, according to this perspective, “sins” are wrong actions or behaviors. In a way, this explanation is correct…as far as it goes. As we shall see, the doesn’t go very far. How do we know what actions or behaviors are wrong? One way is to look for something we did (or didn’t do) that weighs on our minds and makes us feel guilty.

Whether or not we’re aware of it, this is a very poor criterion for judging right and wrong. Our emotions are unreliable guides at best. There’s a truism that goes, “Feelings aren’t facts,” and that applies doubly here. It happens often that we feel guilty for doing things that aren’t wrong. People even tell us, “Don’t feel guilty about that” when they want to reassure us. At the same time, we can do things that are very wrong and not feel the slightest pang of guilt about them. Our old friends the avoidance mechanisms of denial, blame, and escape, and various other ways we rationalize away our bad behaviors function specifically to blunt or silence our guilt feelings. There are other ways to judge our behaviors. The most popular approach is holding our behaviors against an ethical standard. Traditionally, the most popular standard used is the so-called “Ten Commandments.”

Those who want to use the commandments of the Law of Moses, or the Torah as their moral standard, find themselves forced into a particular mindset with unfortunate results. The examination of conscience devolves into a catalog of “sins” like idolatry, breaking the Sabbath, swearing, disobedience, killing, adultery, lying, and coveting, for example. One issue is that these commandments don’t cover the whole spectrum of human behavior. What about things that aren’t covered by one of the commandments? And how about things like disobedience? The commandment says, “honor your father and your mother.” Does it apply just to parents, or to authority figures, as well? If so, which ones? Another issue is that each of these prohibitions covers a wide range of seriousness. “You shall not kill” certainly covers murder, but how about self-defense? And how about fighting, or just getting angry? What’s a serious sin, and what’s not so serious? In addition, there’s the question of when a behavior crosses over from innocuous to sinful, to seriously sinful. Is saying something untrue by mistake lying? Do “white lies” break the commandment? When does an untruth become a serious sin? We call all this hair-splitting casuistry because it looks at examples of behavior case by case and tries to evaluate the sinfulness of it based on what comes down to some very arbitrary principles. The Pharisees in Jesus’s time were experts at figuring out just how far you could go before you broke a commandment.

Even so, that’s not the most serious problem we have with this approach to an examination of conscience. The main issue is that it reduces moral behavior to mere legalism. What’s bad is what’s against the law. The law becomes the determiner of good and evil. It’s also called formalism, where good and evil are judged solely by appearance. In this system, what we do is judged right or wrong regardless of intention or motivation. Hasn’t anyone ever told you, “That’s a sin!”? Anyone who has used this archaic form of self-evaluation knows the result: a “laundry list” of supposedly “wrong” or “sinful” behaviors: “I lied three times. I disobeyed my parents twice. I stole a candy bar. I used the name of God in vain,” and so on. This approach is useful if we want to convince ourselves that we’re fallible human beings, but it doesn’t do anything to expose truly immoral behavior or treat its causes, mental, emotional, or spiritual.

There’s an easier way to take a moral inventory, but it’s somewhat more complex and takes a lot more introspection. Step 4 asks us to look at our faults and failings from a double perspective: resentments and fears.

Here’s the idea behind it: when failure came, we reacted to it. We became upset. The less we understood and took responsibility for our failures, the more upset we became. Residual anger and resentment derive from unresolved conflict either within us or between us and others. We’ve been prevented from getting our way. By taking stock of our resentments past and present, we can highlight the trouble spots in our behavior. Similarly, when we face the possibility of future failures, we become fearful. Fear derives from the possibility that we will not receive what we need or want. By examining our fears, we can discover how our appetites for wealth, power, and prestige may be out of balance. In short, our resentments look to past unmet desires while our fears look toward future ones.

Here’s another important difference between a mental examination of conscience and a written moral inventory. Writing this inventory is not optional, because writing uses a different part of our brains. It literally makes an impression. Let’s look now at resentments and then fears.

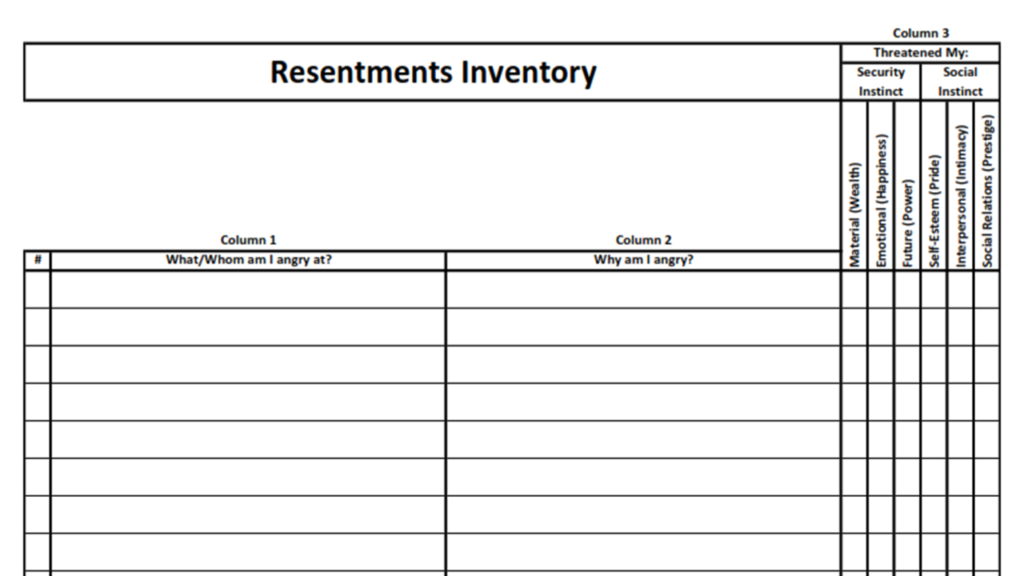

For many years, people have been using a resentments inventory chart to record them. I’ve taken the best of what I’ve found and created a version for you to use as you learn to navigate this step.

On this form, we’re going to record what we’re angry or resentful about in Column 1. Number each entry in the far-left column for later use. You may fill the form either vertically (one column at a time) or horizontally (completing each row before going on to the next). In Column 2, enter your reasons for being angry or resentful. What happened, or didn’t happen that upset you? Were you treated badly?

The third column provides reasons for why the listed event upset you. Let’s briefly look at each column. The first three columns are connected to our individual need for security (self-preservation).

Material Security includes all those physical items you want to have in order to live or live well. It includes the necessities of food, clothing, and shelter, but goes beyond that. The concept of wealth includes not only our needs but also our wants. Did what happened threaten to take away some of your possessions? Is that what made you angry?

Emotional Security addresses our feelings of being safe, secure, and happy in our environment. This could include our capacity for the pursuit of happiness. Did what happened threaten your happiness? Is that what made you angry?

Future Security considers all those things necessary to provide for ourselves and our dependents into the future. It includes the power to bring to fulfillment our plans, designs, and projects that could provide you with material and emotional security. Did what happened threaten to derail your plans and to thwart your goals? Is that what made you angry?

The fourth through sixth columns address our social needs.

Self-esteem refers to our feelings about ourselves vis-à-vis the rest of the world. It’s our sense of pride in ourselves, who we are, and what we’ve accomplished. It’s our sense of being worthy, capable, and adequate to the task of living successfully. Did what happened make you feel less-than, incompetent, stupid, unworthy, or ashamed? Is that what made you angry?

Interpersonal Relations looks at how we function one-on-one. It’s how we create and maintain intimacy in our lives with friends, relatives, and loved ones. It considers our sense of honor and decency regarding others, and our capacity to trust and be vulnerable to others. Did what happened make you feel lied to, cheated, disrespected, or taken advantage of? Is that what made you angry?

Social Relations refers to our standing in the community. We deserve to be respected, not just for what we’ve accomplished, but for who we are. We strive to maintain our prestige in the social realm. Did what happened make you feel embarrassed in front of your peers, put down, disrespected, dishonored, or discriminated against?

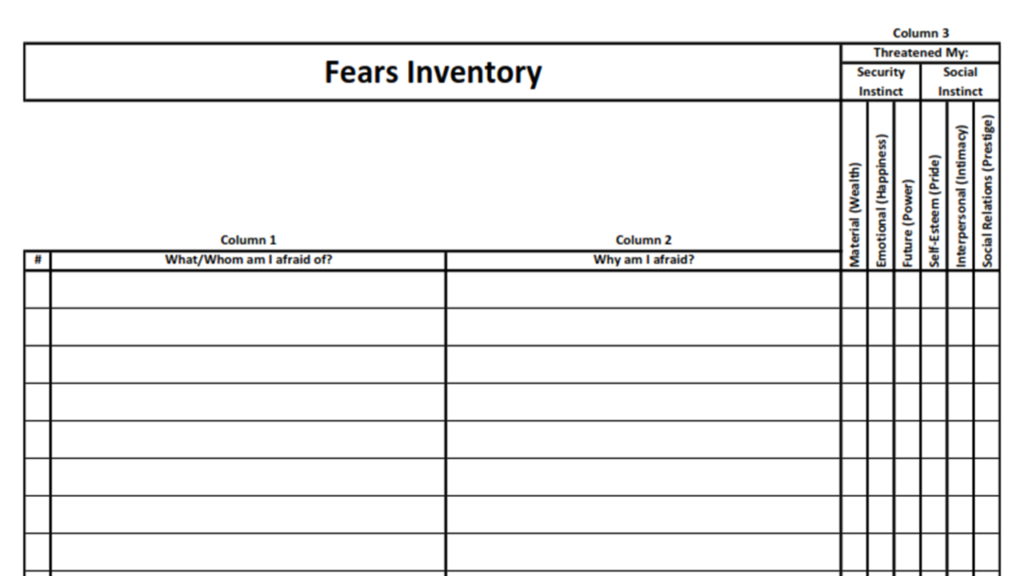

Next, we turn to the fears inventory form.

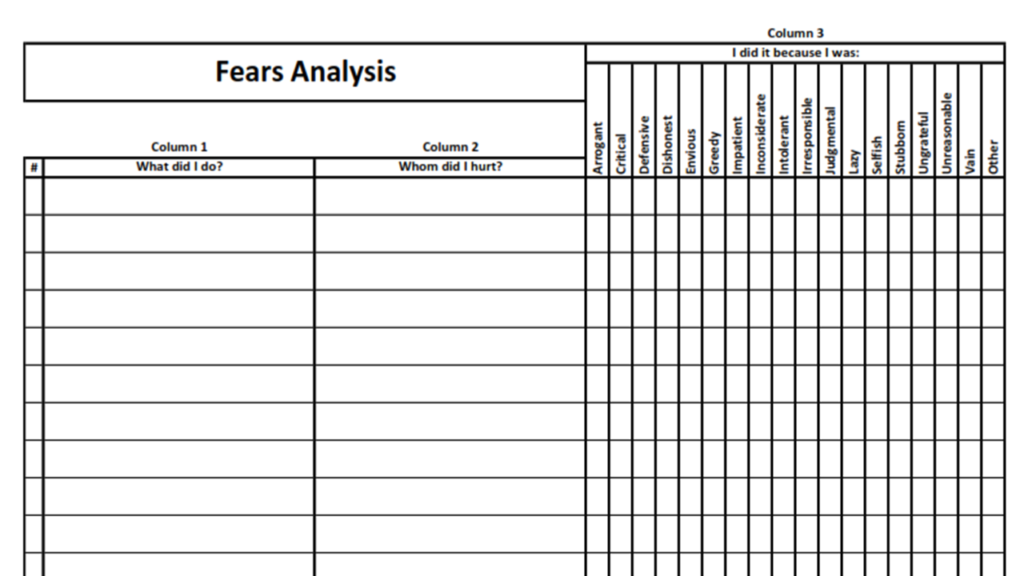

As you can see, the Fears Inventory looks exactly like the Resentments Inventory, except for the questions in columns one and two. You fill this out exactly as you did the first form, numbering each entry in the left-hand column. This time, you’re going to ask yourself what or whom are you afraid of, and why. Remember that our fears come from insecurities about our future security and social relationships. Put a checkmark in each square from Column 3 that relates to how your fear threatens you.

Download your copies of the Resentments and Fears Inventories here. You can download the forms as a fillable Excel worksheet (.xlsx) or printable Portable Document Format (.pdf) sheets.

Portable Document Format (.pdf) Resentments Inventory

Portable Document Format (.pdf) Fears Inventory

Excel Workbook (.xlsx) Both Inventories

After you’ve completed both inventories (and take your time doing this), you’ll be ready to move on to the second phase of your moral inventory. Notice that, for now, you have only created a list of resentments and fears and their causes. There’s no “laundry list” of “sins.” Do not go on to the second phase of the inventory until you’ve finished this first phase to your satisfaction.

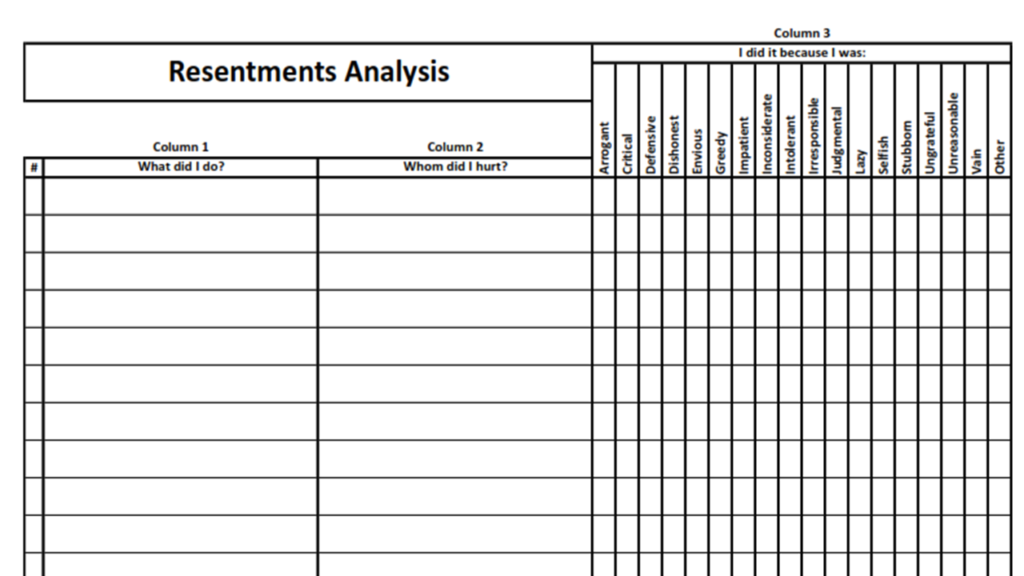

In this next phase, your moral inventory will turn the tables on you, and you should learn a great deal new about yourself. Here is the Resentment Analysis sheet that you’ll be working with:

The shocking truth about your moral inventory is that, for every resentment and every fear that you listed on your inventory sheets, there is some action or behavior of yours that either caused it, contributed to it, or resulted from it. Take your Resentments Inventory and, for every entry, place the number of that entry in the first column of the Resentment Analysis sheet. You will probably find that you will need multiple lines for each of your Inventory entries. In Column 1 list what you did either to cause the situation or in response to the situation. Put whatever “they” did entirely out of your mind. You’re not taking their inventory. Focus solely on you and your attitudes and actions. In column 2, enter the names of people or institutions that you harmed by your actions. In Column 3, check off as many “reasons” for your behavior as may apply. If you can think of a character flaw other than those we’ve listed, check “Other” and make a note of what it is.

Once you’ve finished analyzing your resentments, you can take your Fears Inventory and do the same thing on the Fears Analysis sheets. When you’ve completed your analysis of both your resentments and your fears, you/ll find that you have in front of you the most complete list of most of the wrongs, faults, and failings of your life. Obviously, you will not have to repeat this extensive inventory and analysis often. We’ll talk about that in greater detail when we cover Step 10 in session 6. At this point, we have completed Step 4.

You can now download the Resentments and Fears Analysis sheets from the website to work on them after you’ve finished your inventory.

Portable Document Format (.pdf) Resentments Analysis

Portable Document Format (.pdf) Fears Analysis

Excel Workbook (.xlsx) Both Analyses