Covenant of Life and Love

Twenty-Seventh Sunday Scripture Readings

I have to admit that whenever this passage from the gospels is read, there is some fancy tap-dancing to be done around Christian communities. Although Jesus’s pronouncement on the indissolubility of marriage is given in the context of both the Law of Moses and rabbinical tradition on one hand and Roman civil law on the other, neither background source contains anything like Jesus’s pronouncement on the subject. It’s unique in its strictness and, because of that, it has spawned whole libraries full of commentaries on Christian marriage. As a result, Christian communities and traditions over the centuries have been unable to agree on how this pronouncement should be lived out in practice. Even the strictest literalists have had to adapt. Every time people try to impose a narrow and literal interpretation on it, reality comes calling.

There is no doubt that this pronouncement has led to untold pain and heartache. Yet we can’t honestly say that no good at all has come from it. It has forced Christians from the beginning to put marriage and human relationships on the dissecting board and under the microscope. Would we have even seen a spiritual dimension to marriage if we hadn’t had to try to reconcile the irreconcilable? Most likely not.

Of all the branches of Christianity, our own Roman Catholic tradition has been the most faithful to the literal words of the gospel. Every other Christian denomination has allowed divorce—the dissolution of marriage—and remarriage under certain circumstances. Even then, people who’ve suffered the pain of divorce have frequently become the target of opprobrium, as if their plight had necessarily been the result of some moral failing on their part. Allowing divorce “because of the hardness of [our] hearts” hasn’t proved to be an ideal solution, either.

Historically, marriage was simply seen as a social and legal contract that determined property ownership and inheritance. Marriages were arranged by families to ensure the continuation of their families, and their families’ wealth. Dissolution of the partnership was allowed so long as the property and inheritance issues were appropriately settled. Only recently has love entered into the picture. In a sense, the very nature of marriage has evolved. Now, for most people in our culture, being together is the primary reason for marrying, while property and even children have become secondary considerations.

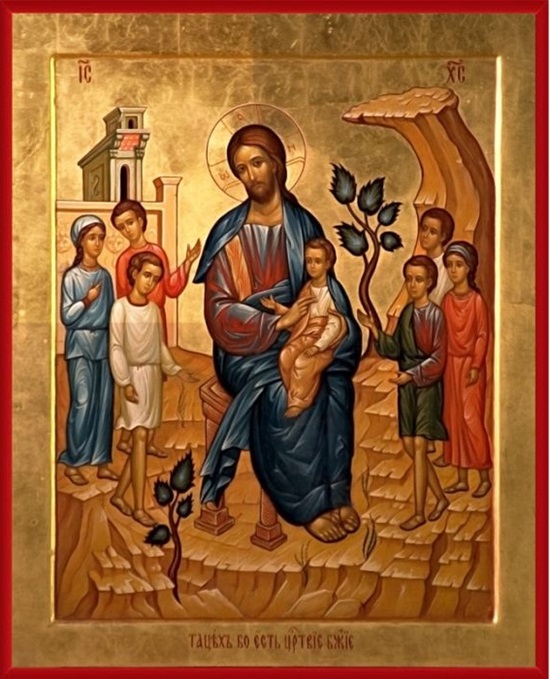

For Christians, Jesus’s pronouncement elevated all that to a higher level—a spiritual level. He spoke of it as primarily a spiritual union. He acknowledged the spiritual impact that entering into a marriage covenant would have on both of the partners. If there’s any sense of commitment at all, the individuals are thereby changed. Once people enter into that covenant, nothing is the same. If anything, in that sense, marriage is permanent. One can never erase that history. It changes both people and affects everything that comes after it, whether the union endures or not. Marriage is more than just a mutual agreement or legal contract. It is transformative, for good or ill.

Believe it or not, contrary to popular opinion, our church has actually been at the forefront, developing a workable theology of marriage, starting with a definition of Christian marriage. The Second Vatican Council redefined marriage as no longer a mere contract when it said, “The intimate partnership of life and the love which constitutes the married state has been established by the creator and endowed by him with its own proper laws: it is rooted in the contract of the partners, that is, in their irrevocable personal consent.”[1] A consortium vitae—an intimate partnership of life and love—that is the spiritual union in marriage that Saint Paul wrote about in his letter to the Ephesians [5:32], when he quoted Genesis and then added, “This is a great mystery, but I speak in reference to Christ and the church.” The one is a reflection of the other.

We recognize that not every union comes up to that high standard that it becomes the image of the union of Christ and his Body, the Church. So, instead of pretending that the Church can step in from the outside and somehow undo the commitment the couple made to each other, it simply recognizes in a failed community of life and love that factors unrecognized by the couple at the time of their commitment were present that prevented their union from achieving all that they had intended it to become.

How often we commit ourselves to projects and causes that are both important and worthy of our time and efforts, only to find that there are factors in play over which we have little control that make it impossible to succeed without doing harm to ourselves and others. From this perspective, many so-called “failed marriages” may not be failures at all. Which is the greater failure, to recognize the futility of going forward and to cut our losses and change direction, or to keep investing physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual energy in a hopeless pursuit that can only cause further damage?

With this recognition, our church acknowledges that there are always factors in play in every failed relationship that would prevent it from ever truly becoming what the partners wanted it to be. The church does its best to identify what those factors are and, as a spiritual support to both partners, help them to acknowledge with sadness that their human frailties have once again gotten the better of them. This is not to assign blame but to provide a perspective that may give them a chance to grow and avoid those pitfalls in the future. That’s also why, whenever we find a union that has overcome the forces that keep us separated from one another, we joyfully acknowledge that, although imperfect, it’s a sign for us that the grace of God is always present and active in our midst when the two have, in fact, become one flesh, one spirit. That makes it a sign—a sacrament—that, despite the weaknesses and imperfections in the Christian community we call the Church, Christ will never abandon his body but continues to call it to become an ever more perfect

[1] Second Vatican Council, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes), §48.