Session 4: Creation IB—The Animate World

First, a brief review. From the moment we begin to read the words, “In the beginning…,” we are immediately transported out of the physical world of space and time and into sacred space and sacred time.

The beginning of the Book of Genesis relies heavily on the images and concepts found in the ancient Mesopotamian creation myths (like the Enuma Elish) to tell its stories. The primordial chaos is represented by unfathomable and formless waters.

In Genesis, as in the Enuma Elish, creation does not come out of nothing, but everything is formed out of chaos and is given names in order to exist. Knowing something’s name gives one power over it. How much more so the power to give something its name. In the Semitic languages, the word for ‘word’ is the same as the word for ‘thing.’ God creates out of chaos simply by the word of his command and his power to give things their name. No-thing becomes some-thing.

The first five books of our Bible are called the Torah or the Pentateuch. It’s the result of centuries of compiled stories. There are four main sources. The oldest source is called the Elohist which had its origins in the northern Kingdom of Israel. It uses Elohim as its preferred title for God. It focuses on the capital city of Samaria and the shrines throughout the kingdom where Elohim was worshiped. The style is somewhat flat and bland. When the Kingdom of Israel was overrun by the Assyrians, the Elohist writings were carried by the exiles south to the Kingdom of Judah. A century later, we find the source called the Yahwist from the southern Kingdom of Judah. The Yahwist prefers to use the proper name of God, Yahweh, in most of its writings. It focuses on Jerusalem, the kingly line of David, and the Temple. The Yahwist is a skilled storyteller and shows deep insights into human nature. The third source is the Deuteronomist who was the source of the Book of Deuteronomy. The latest source, dating from the return to Jerusalem from exile in Babylon, is called the Priestly tradition. Writings from this source are highly structured and scientific (within the limitations of the science of the time). It’s concerned with re-establishing orthodox Jewish beliefs and practices such as sacrifice and Temple worship. The first chapter of Genesis is clearly the work of the Priestly source.

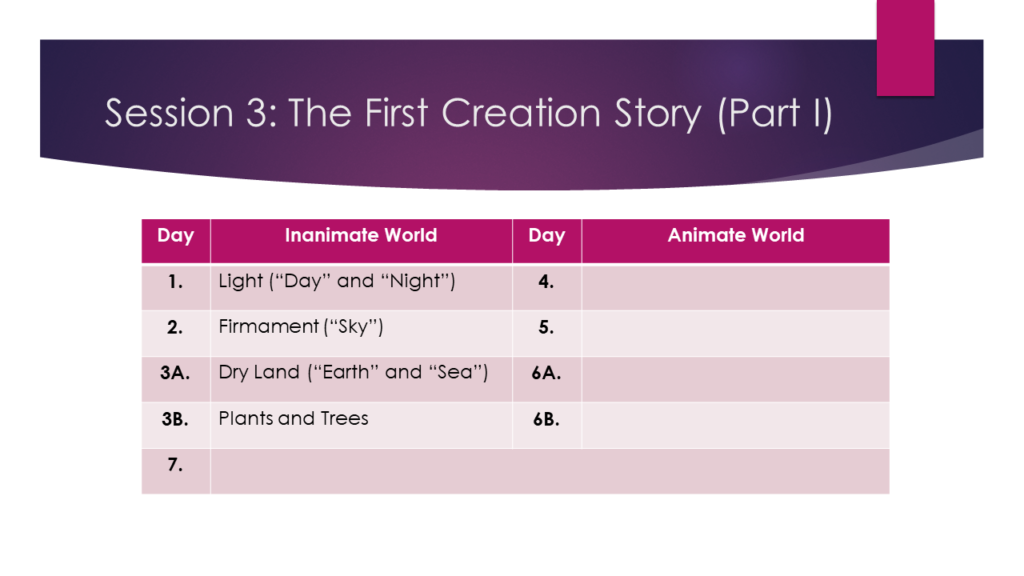

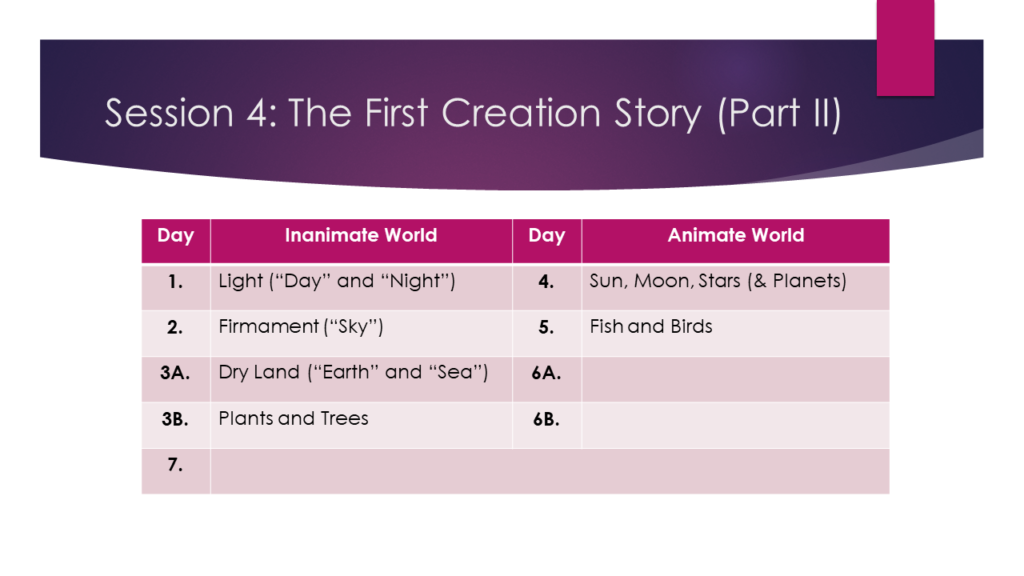

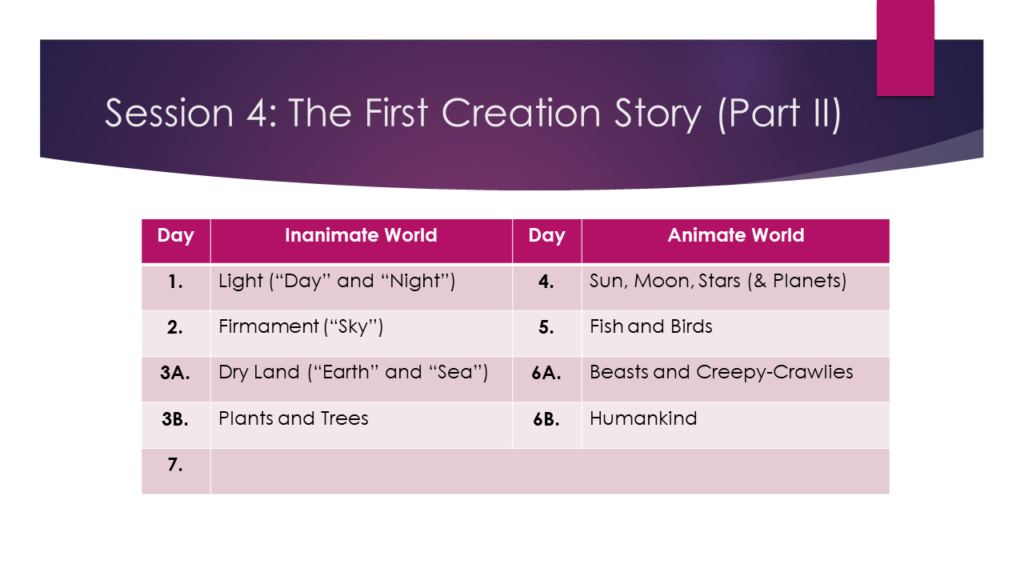

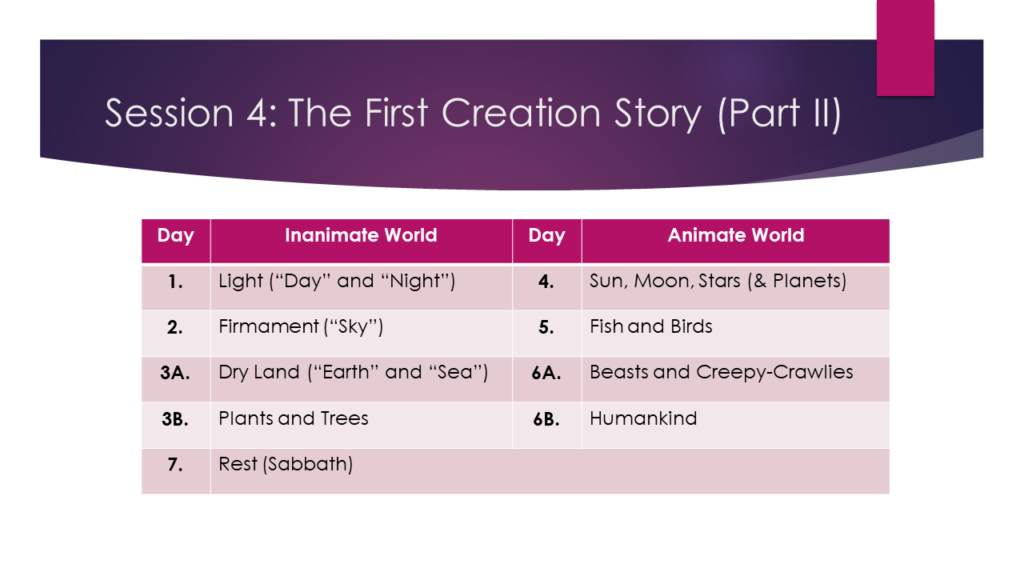

The structure begins. God creates light and separates it from darkness. These are things, not gods. He names the light “day” and the darkness “night.” These are not periods of time. We are in sacred time, after all. These are merely markers to delimit the segments that the Priestly authors used to structure creation. Light is the first segment. God then separates the primordial waters into two by a dome, which he names “sky.” There is no struggle, no battle, no weapons, no war. The sky is a thing, not a god, and it is the second segment. Next, God calls the dry land out of the primordial waters and forms them together into a basin. He calls the dry land “earth” and the basin of waters, “sea,” and so, they exist. The “earth” and “sea” are assigned to the third segment.

Then God has the earth bring forth plants and trees. They’re not like “earth.” According to the Priestly scientific understanding, living things breathe, move, and have blood. Plants and trees do not obviously breath, they only sort-of move, and they don’t have blood. Therefore, they’re not really alive. Yet they have seeds and reproduce. They are special. So, they, too are assigned to the third segment, as a special case.

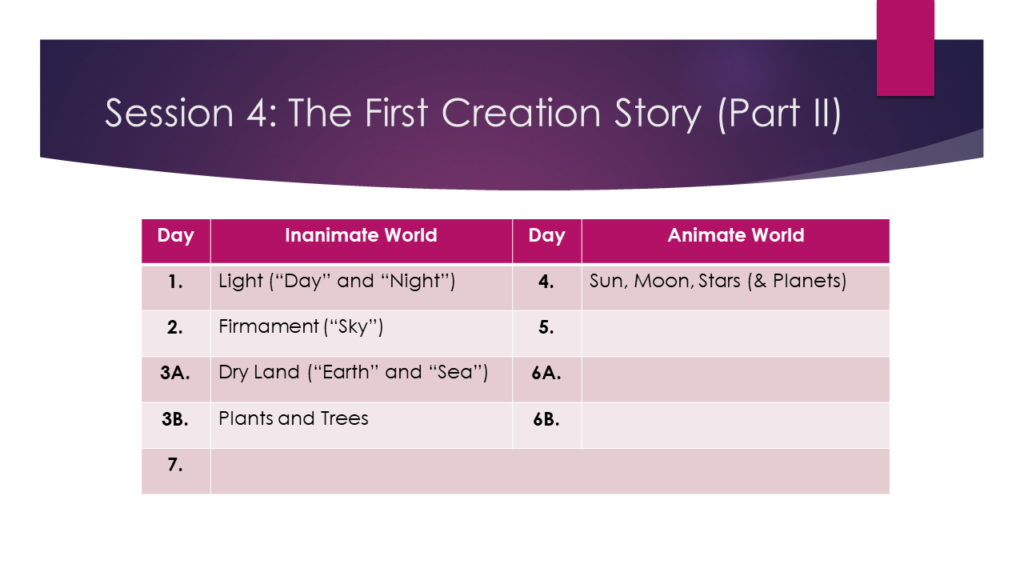

We remember from the Enuma Elish that the gods were created first, then the hero-God Marduk created everything else. For practically all ancient peoples, the sun, moon, stars, and planets were gods. They had proper names. You can read the description of the creation of the sun, moon, and stars from the Enuma Elish on page 13 of the text. A link to the text can be found in the transcript of this session [click here]. According to the ancient texts, the celestial bodies ruled the earth and controlled human destiny. Once again, the Priestly author reduces their status to objects that serve a purpose. They’re installed in the dome of the sky as timekeepers. All that they control is the time of day and night, and they serve to mark the seasons. They have no bearing on human destiny. There’s no astrology in the Priestly cosmogony. And the lights are fabricated. The word used to describe God’s work here is אשׂה (asah), meaning ‘to fabricate,’ and yet, they are alive. All the celestial bodies move. They’re too far away to be able to determine whether they breathe or bleed or not. So, in the Priestly science, they are living beings.

Here we see the fourth segment marker. The living lights provide a great celestial clock from within the dome of the sky.

Once again, the Priestly source has demythologized the ancient stories. There is no “mother sea,” no “mother earth,” and no “mother sky.” As always, there’s simply God’s spoken command and the sea and the sky team with living things: fish and birds. They breathe, they move, they bleed…and they reproduce. God doesn’t form these creatures, he “creates” them. The word used here is ברא (bara’)—the word we encountered in the first verse when we read, “In the beginning, God created…” Since the fish and birds are living, God blesses them and gives them a command to be fertile and multiply. We’re observing a crescendo of creativity.

Here we have the fifth segment marker. As living lights in the firmament completed the formation of light and dark, day and night, so the fish and birds complete the formation of the sky in the midst of the waters. Once again, there are no gods. Even the sea monsters are simply creatures under the dominion of God the creator.

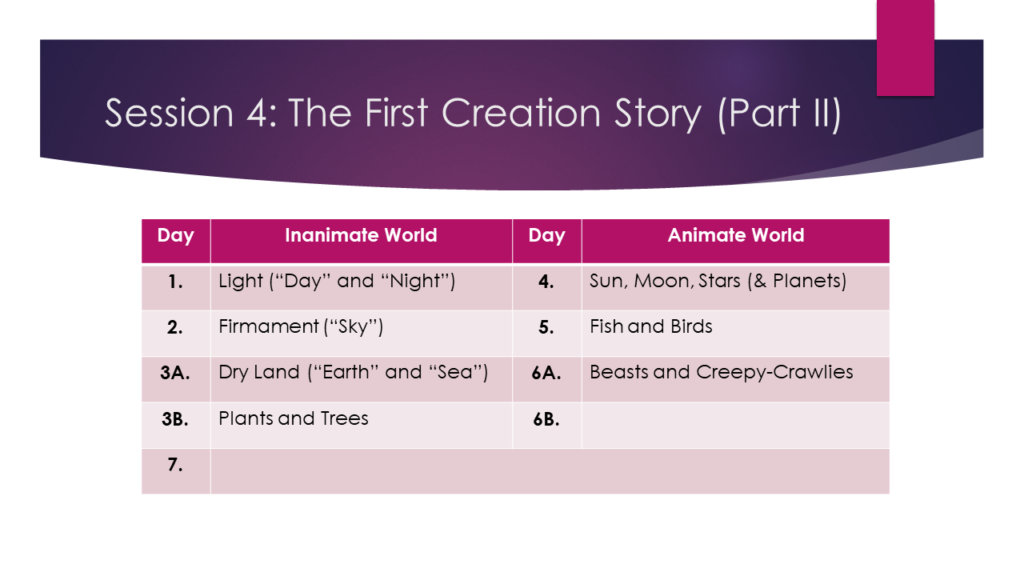

The waters and the sky are already teeming with life. All that remains inanimate is the earth. Once again, God has the earth bring forth living beings by his command—all creatures, great and small, wild and tame, and creepy-crawlies. Don’t let the anachronism trip you up. The Priestly tradition isn’t concerned with who tamed the wild animals or when they were tamed. The point is that they’re all there. For the Priestly authors, the universe was static. The way it is now is the way it was from the beginning and the way it always will be. It would be many millennia before anyone conceived of an evolving universe.

Although we’re obviously into the sixth segment, we’re not yet given the segment marker, “Evening came and morning followed…” However, we can now see the perfect parallel between the emergence of dry land—the “earth”—and its bringing forth animal and insect life.

Just as we experienced a second creation of something special in the third segment (day three)—plants and trees—so, in the parallel segment on day six we find the creation of something very special: humankind. We’re going to have to spend a little time looking at this verse in greater detail.

“And God said…” “God” is Elohim.

Elohim itself is a plural form of the noun El. El is the word for god—any god. It is sometimes used for Yahweh, as in the name El Shaddai, meaning ‘God Almighty.’ It’s also the same root we find in the Arabic Allah. Elohim is the plural and it’s used to refer to the gods of the pagan nations. But it’s also the common word used to render the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. This may be what is called the plural of fullness. Not only that, sometimes in the Hebrew Scriptures, Elohim is used to refer to the council of heavenly beings, or even angels.

So, in our passage, when Elohim says, “Let us make human beings…” who is this “us”? Scholars are not entirely sure. It could be a throw-back to the ancient creation stories where the gods are gathered in council. But the Priestly authors are very careful about their work and it’s not reasonable to think that they would have just let that reference to other gods go by. Or it could be what we call the “imperial we” that monarchs used to use to refer to themselves. Remember Queen Victoria’s famous—if apocryphal— “We are not amused?” But this usage has never been seen in contemporary biblical texts. It’s doubtful that this was the case. That leaves two possibilities: either God is addressing the heavenly host, or simply referring to himself as “we,” the same way we do. Haven’t you ever said to yourself, “It’s getting late, we’d better get a move on”?

The next word we have to look at is what’s been translated as “human beings.” Other translations have “Let us make man…” The Hebrew word is אדם (’adam). Adam means humankind. Likewise, האדם (ha’adam) means “the human.” It’s not a proper name, so ’adam refers to humanity, not an individual. This is critically important for the understanding of the next phrase.

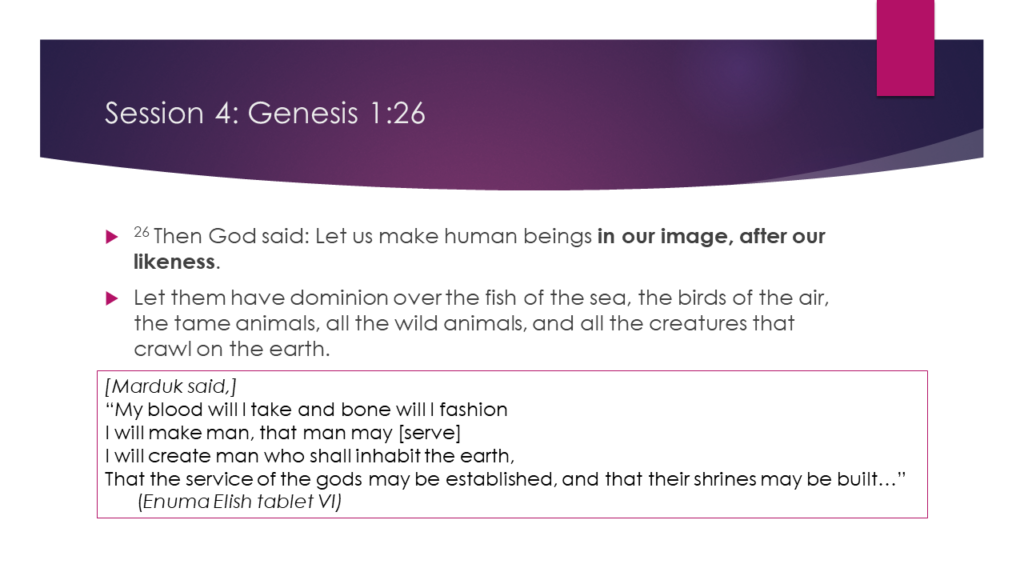

“…in our image, after our likeness…” This is revolutionary in the context of the ancient myths. Here’s how the Enuma Elish describes the creation of humanity:

For the creation myths of almost all ancient peoples, humanity was the plaything of the gods for their amusement or service. This is not the case for the Priestly author. The word translated “image” in our text means a resemblance or something modeled after something else. The word translated “likeness” means an exact replica or reproduction. It’s the word used to describe statues or icons. What the author is referring to is not the human form as the image of God, but that aspect of humanity that sets us apart from the rest of creation. That is precisely our consciousness of creaturehood. It’s that consciousness that makes us ask where we came from and seek out our origins, our purpose, and our destiny. That is where the image of God resides. For the Priestly author, we humans are not playthings of the gods, but we carry within us a spark of the divine.

The next term we need to look at is “dominion.” Notice that the text says, “let them” not “let him.” We are still talking about humanity, not any individual. Dominion is a constitutive feature of kingship. To further distance this creation story from the ancient myths, not only did humanity possess a spark of the divine so that we are not playthings of the gods, we have also been given a divinely-inspired kingly reign over all living things. However, our dominion was not intended to be absolute, as we shall soon see. We have not finished with this chapter quite yet.

The dominion that God gave humanity was to be exercised in a reasonable and ordered manner as the Priestly tradition described it. Genesis tries to imagine humanity not as what it has made of itself, but as what God had intended it to be. It is admittedly an idealized version. Here’s how Scripture scholar Bruce Vawter describes it:

“The possibility…is that power should be exercised in the cause of right and justice and equity, the way that God exercised it in Israel’s history and the way that he intended that man[kind] should exercise it as his surrogate. This means, in modern terms, a rational, sensible, humane, intelligent, and thoughtful ordering of God’s ordered world, dispensing correctives where they are necessary and furthering propriety where it is clearly proper. Dominion is not a license to caprice and tyranny but, in its best sense, a challenge to responsibility and the duty to make right prevail.”[1]

In our text from Genesis, the gift of dominion is repeated, this time as a blessing. Also, only in this segment of creation does the author make explicit “Male and female he created them.” It’s possible that was added to make it more general as a response to the second creation story from the Yahwist, where we’re presented with only one man and one woman.

This passage makes explicit the limitations placed on humanity’s dominion. Everyone knows that this passage gives all the plants and trees to the other living things for food, but many don’t appreciate the impact of this passage. Remember that plants and trees are not exactly living things. They have no observable breath, they only sort of move, and they have sap not blood. That’s why they’re given to all living things as food. This is an implicit prohibition against spilling blood. No truly living thing was to kill or feed on any other living thing. This is the Priestly description of paradise—the way things were meant to be. There’s also an implied suggestion that, someday, things will return to the way they once were. This is humanity’s unrealized ideal.

Now, at last, the marker for the sixth segment can be given and the chart of creation is complete. The two columns, inanimate and animate, are in perfect parallel. You have to admit that this order and structure was a remarkable accomplishment for the Priestly authors, especially when you consider the raw materials they had to work with.

In these verses, we have a rare anthropomorphism that the Priestly authors permitted themselves. This story was composed after the Babylonian exile. During that time, nearly all the Jewish institutions had been destroyed, including the temple in Jerusalem and the line of kings descended from King David. The people of the northern Kingdom of Israel had lost their identity when the Assyrians scattered and mixed them with other peoples. The southern Kingdom of Judah was not about to let that happen to them. The priestly caste was charged with not only maintaining Jewish history, literature, and institutions, but also the maintenance of their Jewish identity. That identity hinged on two practices in particular: circumcision and observance of the Sabbath. Indeed, the word “sabbath” means “rest.”

Observance of the Sabbath was a requirement for the Jewish nation, but they deemed it applicable to everyone. So here, at the end of the Priestly creation story, after the creation of humanity, God is shown observing the Sabbath as a model for everyone. In fact, in the Kingdom of Judah, everyone observed the Sabbath, Jews and foreigners alike. The text states not only that God rested from the work he had been doing, but also that he blessed it and made it holy. This is the way the Priestly authors expressed that the Sabbath was an entry into sacred time. And so, we have come full circle from the beginning when there was only sacred time, to the completion where we return to sacred time.

This marker completes the seven segments.

Next week, we will begin again. We will enter into sacred time with a different guide: this time, the Yahwist author. Many people are unaware that there are two separate and distinct creation stories in Genesis, one by the Priestly authors and a second, older one, by the Yahwist. We’ll be paying close attention to the radical differences between these two traditions. Until then, thank you again for following along with us.

Click Here for Session Video

[1] Bruce Vawter, On Genesis a New Reading, New York: Doubleday & Co., Inc., 1977, p. 59.