Session 5: Keeping Chaos at Bay

So long as we remain in the Book of Genesis, we’ll need to remember that we remain outside the limitations of physical space and time, and in the realm of sacred space where there is neither location nor dimensions and sacred time where this is neither duration nor past nor future, only present.

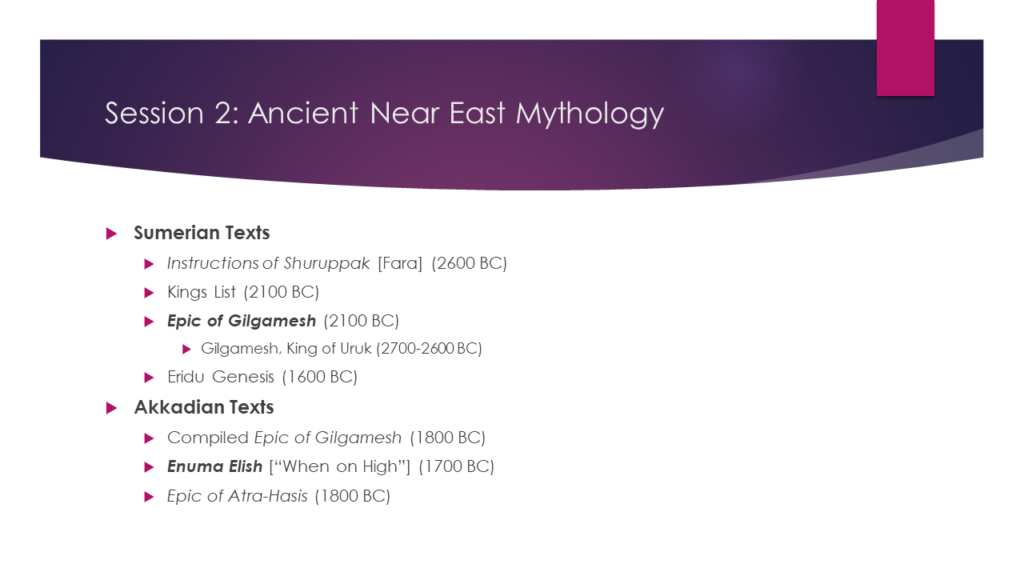

Sacred space and time define the world of myth where language attempts to express deeper realities, like the origins of things. In the first creation story from Genesis, we referred to passages from the Enuma Elish that were borrowed to describe how everything came to be.

The first creation story came from the Priestly tradition in the sixth century BC after the return to Jerusalem from exile in Babylon. The second creation story, which we begin today, derives from the work of the Yahwist author, about a century earlier.

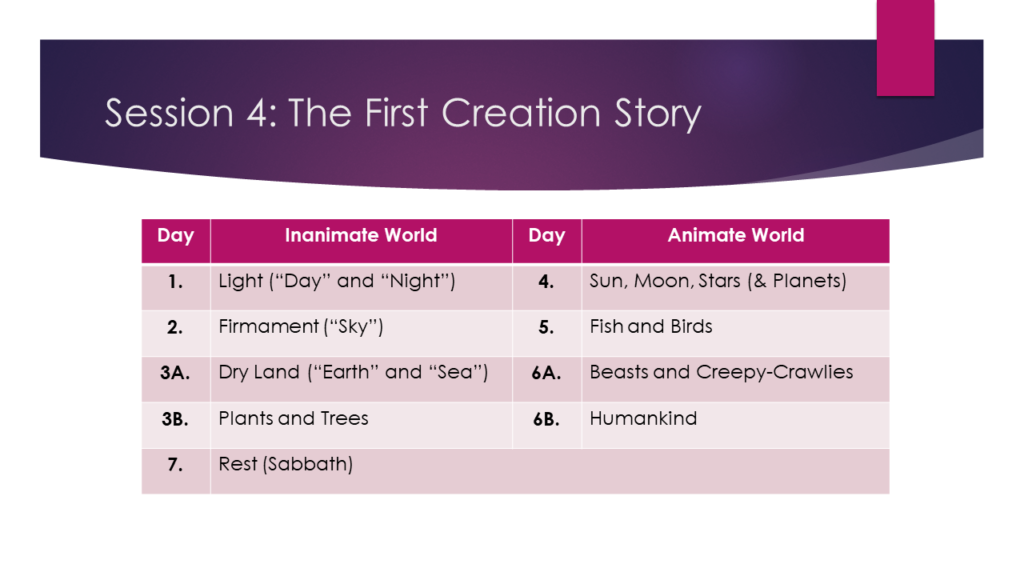

The Priestly tradition created a very structured and ordered schema for the creation story—a schema we saw in detail. Apart from the primordial waters, the Priestly tradition was very diligent about demythologizing creation. Except for God resting on the Sabbath, they were also careful to avoid anthropomorphizing when describing God and his actions.

The first half of verse 4 is problematic. On one hand, it seems to provide a good transition from the first creation story to the second. OR it could be the conclusion of the first creation story. There’s one word in this half-verse that makes us think it belongs with the Priestly tradition rather than with the Yahwist.

The word translated here by “story” is תולדת (toledot). It means “generations” and it provides a genealogy of the universe. Genealogies occur quite often in the Scriptures. The Priestly tradition provides us with no less than seven in the Book of Genesis, if we count this as one of them. What was the purpose of these genealogies? They trace the origins of important people. They were especially important to the Priestly authors because they were concerned with providing an orderly structure, as well as providing the ancestry of the Patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) and giving them legitimacy by positioning them squarely within God’s creative work. If this text was, in fact, written by the Priestly author, it may have been the original first line of the Book of Genesis, and it may have been moved here by the Redactor to form a bridge between the two creation stories.

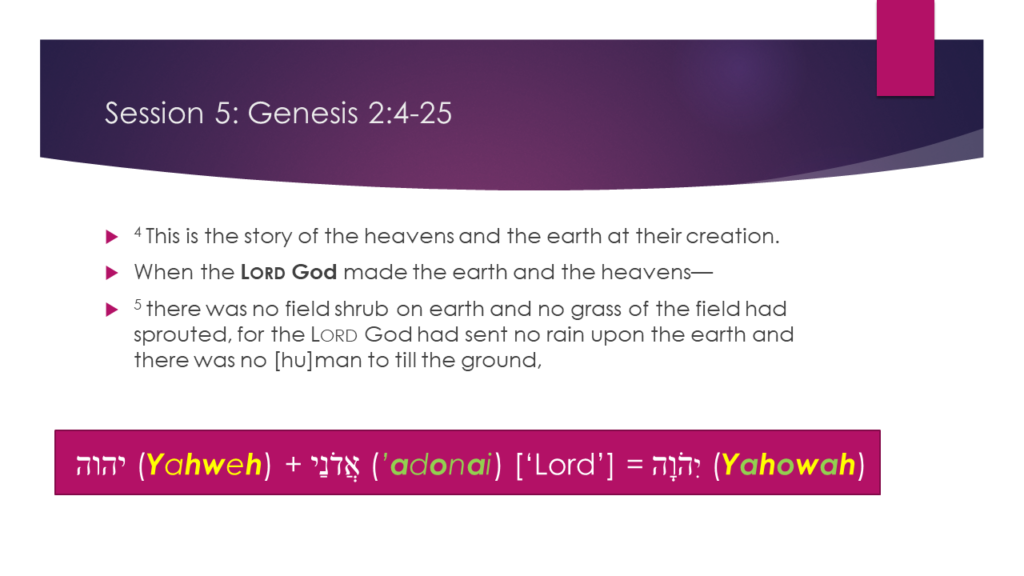

The next phrase we want to be aware of is translated “the Lord God,” with “Lord” written in small capitals. This is to indicate to you that the original reads, “Yahweh,” the proper name for God. Can you figure out why this is done that way? Let me give you a hint. It’s following the Hebrew practice. To avoid ever saying or reading the name “Yahweh,” whenever readers would come to the name in Hebrew, they would replace it with אֲדֹנַי (’adonai) meaning “Lord.”

To help the reader remember to make the substitution, they wrote the consonants of Yahweh with the vowels of ’adonai, making the impossible combination “Yahowah,” which was never meant to be read that way. In English, we get the bastardized word, “Jehovah.” Why was it so important not to speak Yahweh’s name? If you think about it for a bit, you should come up with the answer: to name something gives you power over it. So, to speak the name of God calls on God—summons God. You don’t ever want to do that frivolously. Therefore, “you shall not take the name of Yahweh, your God, in vain.” That is what that commandment was about, not cussing.

In ancient times, God’s proper name was called out only once a year on the Day of Atonement, and only by the High Priest himself and only in the Holy of Holies in the temple in Jerusalem. While that was happening, all the worshipers outside would yell and create a tremendous din, lest anyone hear the name of God spoken aloud. And, even today, no observant Jew would ever speak the Name. We, however, are no longer under that prohibition, and so, from now on, the proper name of God will appear in the texts on our screen. This is the Yahwist we’re considering, after all.

Let’s move on to the story. Like the Priestly author who followed after him, the Yahwist is not concerned with how things were created. The Yahwist’s story, too, shows God forming creation out of chaos. Here’s how he describes it: take away all humans, all animals, all vegetation…and all water…and what have you got? A desert wilderness. For the Priestly author, chaos was the primordial waters of the creation myths. For the Yahwist, chaos is the uninhabited desert that surrounded him, and which constantly threatened the life and livelihood of the people of Judah. There were two things that made life possible in the desert wilderness: water, and human beings to cultivate the land and grow food.

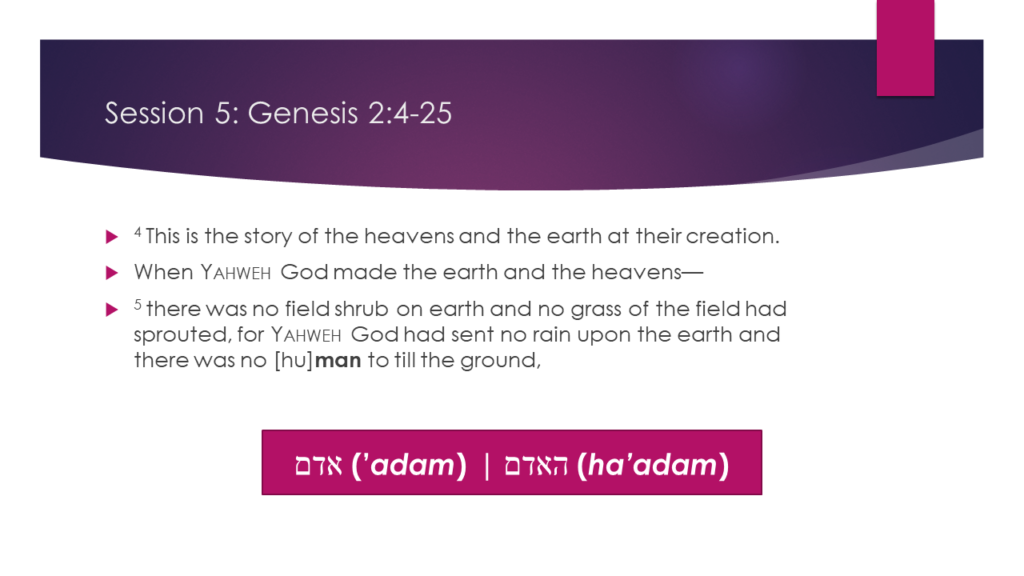

Once again, we must not think of “the man” as an individual. That’s why I’ve turned the word into human to remind you that, although the story talks about “the man,” we must always think of it as a representation of humanity or paradigm for it.

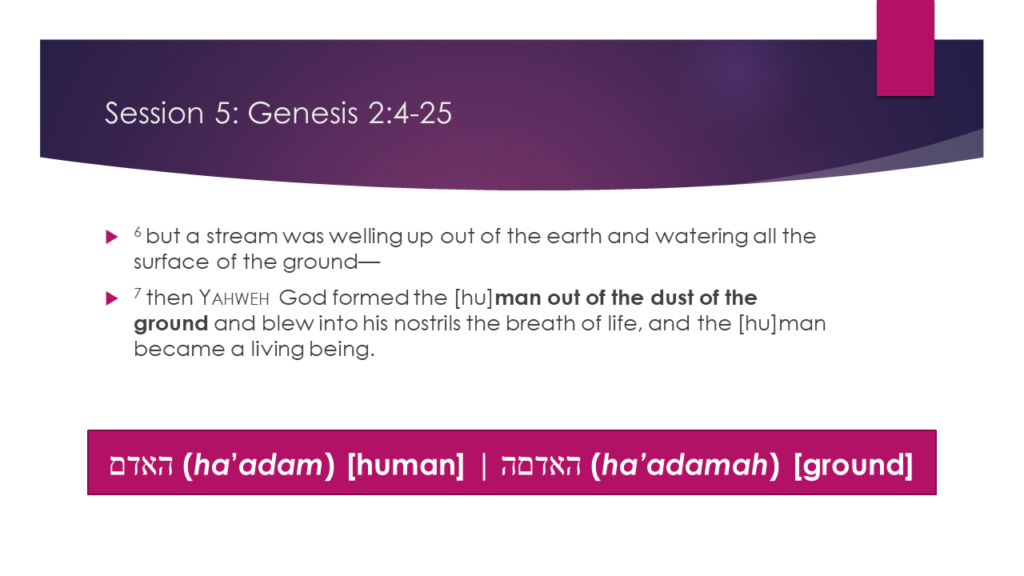

As we saw last time, the word for “human” is ’adam. It can also refer to a male human. Let’s go on.

This is as close as the Yahwist gets to describing the creation of the universe. For him, the material world doesn’t hold much interest. He never asks where the earth came from, or the sky, or even the water that welled up out of the ground. He only notes that it’s there, and that only because water is essential for life. You can see here more hints of the eternal universe—always was and always will be. This is not dogma. This is not science. It doesn’t pretend to explain what “really happened.” The Yahwist isn’t concerned about that (and neither should we be). The truth he’s describing goes much deeper than that.

The author gets right to the point: the place of humanity in the universe. The Yahwist doesn’t hesitate to anthropomorphize God. Here, he shows God like a potter, forming mankind out of the dusty ground and water, making a clay figure and blowing the breath of life into his nostrils. There’s even a play on words here: ha’adam and ha’adamah—the human and the ground. It’s like if we were to play on the words, “human” and “humus,” the soil. The point is that humans are of the soil and will return to the soil. We are formed out of the elements of our home planet, but we only borrow them for a time.

We’ve seen several times in the Priestly text how important the breath of life was to the early Hebrews. Here, Yahweh God not only molds the human out of clay, but he gives his creature breath. The result is that the newly-formed human becomes a living נפשׁ (nephesh). The nephesh is that part of the living human being that descends to Sheol when the flesh of the body dies. Sheol is the abode of the dead: a dark, damp, place, akin to the Greek idea of Hades. All sentient beings (both animals and humans) are said to have nephesh, so, although it’s similar to our concept of “soul,” it’s broader.

God continues to be anthropomorphized. He doesn’t just speak the word and it happens; he plants the trees to form a garden. The image of the garden is somewhat blurred. This may be the result of the Yahwist trying to blend two separate but similar stories. In the one, God continues creation by providing plants and trees, including the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. In the other, there’s a pleasure garden in the east, in Eden, that God has for his recreation, and it includes the tree of life.

Let’s talk about the east and Eden for a moment. Our text was written in what is now Israel. To the east lay the deserts: the Negeb and the deserts of Jordan, Syria and Iraq. Beyond that was the “fertile crescent”—the Tigris-Euphrates River valley—home to the ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, and Babylonian cultures. Chances are that the Yahwist had never personally traveled there. What he knew about it came from the stories that nomadic desert traders brought with them. He heard of plenteous water and an abundance of plants and trees. For him, that kind of richness could only be found “in the east.” Was Eden a real place? If it was, its location has been lost to history. It’s very possible that the name was derived from the Akkadian word that meant “steppe” or “plain.” What intrigued our author was that it’s exactly like the Hebrew word for “pleasure.” Notice that the garden is in Eden. Only later does the name Eden get applied to the garden itself.

Creation continues. The lush plant growth provides food, just as in the first creation story. Plants are not really alive, so they are provided as food to animals and humans. Among those plants and trees are two special ones: the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. We’ll talk about both these trees a little farther along. The tree of the knowledge of good and evil figures prominently in the garden story that follows; the tree of life disappears, only to return at the end of the story. We’ll start with the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, but first, there’s more creating to be done.

The geography of this section is confused. Suffice it to say that the description of the rivers is backward from the way we speak about them. The Yahwist writes that a river rises in Eden and divides into four. That’s going upstream. We would say that four rivers flow together into the territory. Some of these names are unknown: the Pishon river and the Gihon, as well as the territories of Havilah and Cush. Cush was often used to refer to Egypt, but that doesn’t make sense in our Mesopotamian geography. We do know the Tigris and Euphrates, however. They both flow together into the Persian Gulf. That means that, if Eden was a real place, it would have been located somewhere in that area. This isn’t surprising because it’s the location of the Sumerian city of Ur where the Yahwist’s ancestor Abraham originated. Remember that this is a toledot—a genealogy of the Semitic world. We can see traces of historical fact underlying the sacred space called the garden in Eden. Everything else in this section bears the marks of an author who was reporting only what he’d heard from other travelers.

Now, the story gets interesting. The Yahwist has thoroughly anthropomorphized God. God not only created the human out of the dirt like a potter, but he also planted trees. Now he picks the human up and places him among the plants and trees to cultivate the land. Do you remember the Yahwist’s description of chaos? There was no human to cultivate and bring order to it until now.

Finally, God sits the human down to have a little chat. He gives the plants and trees to him for his food. However, he forbids the human to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Well, that’s a bummer. Let’s see what that’s all about.

Before we go any further, you’ll have to put the apple out of your mind. There is no apple. There never was an apple. What we have here in this tree is a sacred object. Remember five sessions ago when we introduced sacred space and sacred time? We also introduced sacred beings (like heros) and sacred objects. Sacred objects have a relationship to physical objects but they exist in sacred space and time. They can serve as doorways to the sacred. Trees have always been considered sacred objects. Gods of all sorts were worshiped by sacred trees and in sacred groves. Gods had trees that were sacred to them. Trees figure prominently throughout the Hebrew Bible as places sacred to Yahweh and places where the prophets went to commune with God. The tree mentioned in our text is one of these sacred objects. It’s a tree, but more than a tree. It’s likely that, when the ancients heard this story, they thought of the trees and groves sacred to the pagan gods around them that they were constantly warned against worshiping.

Now, let’s talk about this tree. It’s the tree of knowledge. As you might expect, it’s not just any knowledge. In the Hebrew mind, when you have knowledge of something—you know its name—you have power over it. The old saying goes, “knowledge is power.” In this case, it’s literally true. To know the name of something—even God—you know its essence and you can control it. So this “tree” is the tree of power. What kind of power?

Power over good and evil. Do you remember in our second session when we introduced the opening verses of Genesis, I pointed out that God created the heavens and the earth? Do you remember that I called that figure of speech that uses the extremes to include everything in-between a merism? Here’s another merism: good and evil. What that includes is everything in-between—all human behavior. In other words, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil represents power over everything. Remember when we spoke about “dominion” when we were discussing the Priestly text? Here it is again in the Yahwistic text. Humanity’s dominion is not absolute. We cannot determine everything. We do not have absolute power. We cannot play God with impunity.

Power and dominion over the world and over our own behavior can be a good thing. But too much of a good thing can be deadly. Power corrupts. Absolute power corrupts absolutely. Playing God is an exercise in futility and arrogance. It’s destructive to our humanity. Like all vice, it carries with its own deadly consequences. The prohibition against eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil—the prohibition against trying to exercise power over everything—is not arbitrary. It’s for our own good.

There are two main points we can glean from this passage. Once again, we are presented with an anthropomorphic God who ruminates about humanity’s social nature. Then, as fabricator-in-chief, he molds animals and birds and brings them to the human. His purpose is to provide humanity with power over these creatures. Once again, we see name-giving as an exercise of power and dominion, although animals are not presented to the human as food. For the Yahwist, the creation of animals and birds is not seriously important. Even the tame animals—the service animals and pets—are not suitable partners for humans. Their creation serves only as a prelude to the formation of woman.

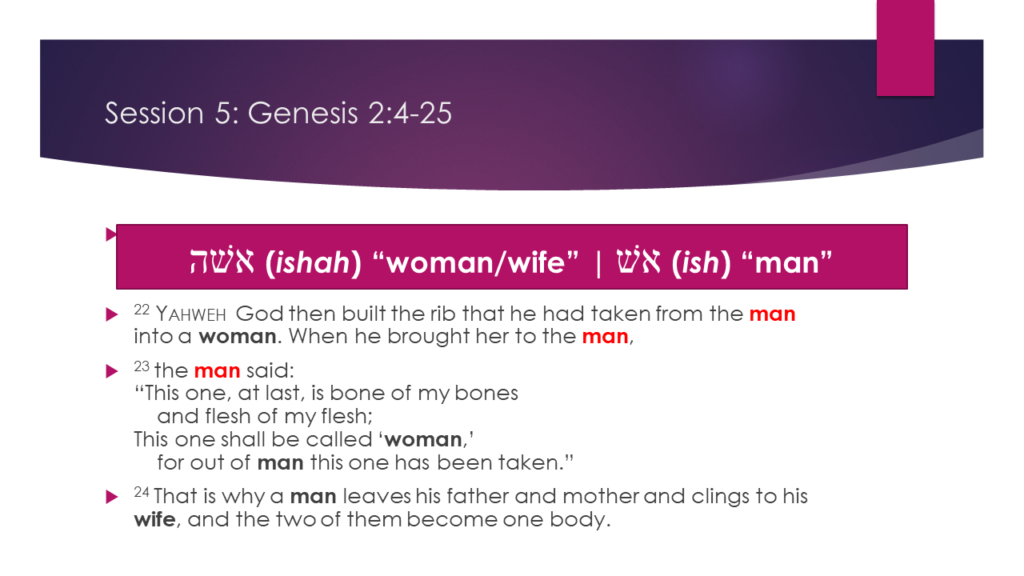

The understanding of the words for the man, האדם ha’adam, now shifts from “humanity” to an individual. The formation of woman from man almost certainly borrows from older myths. There is a hidden wordplay in this passage that came from the original Sumerian version of the story. The word for “rib” in Sumerian is represented by the same symbol that is used to represent the word for “life.” We’ll see next time that the woman’s proper name is indeed a cognate of the Hebrew word for “life.”

In this passage, the vocabulary changes. Where I have highlighted the text in red, we have our old standby word for human, ’adam. After the formation of the woman from the flesh of the man, the wording changes. The term used for “woman” is אשׁה (’ishah), meaning a “female,” while term used for “man” is אשׁ (’ish), meaning a male.

This highlights the equality of their relationship. Here, nothing at all is made of the fact that the man names her. It’s as if the name for woman came out of the name for man in the same way as the woman herself was taken out of the man. The accent here is on the similarities and parallels between the sexes, not the differences.

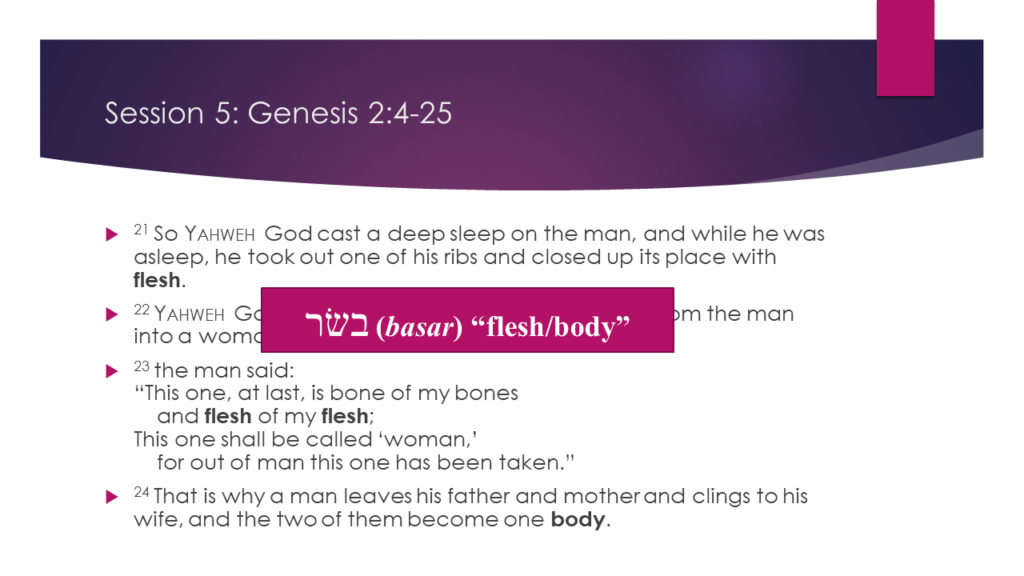

The word highlighted on your screen is the Hebrew word בשׂר (basar). Biblical Hebrew had no word for “body.” And the word basar was much broader in meaning than just “flesh” or “meat.” It signified a person’s very being, their identity, their heart and soul. The union of man and woman, according to the Yahwist, is an absolute equality. The Yahwist wasn’t commenting on the exclusivity of the union—after all, polygamy was a fact of life in ancient Israel—but it highlighted the equality of the partners in an age where elsewhere women were considered property. In Israel, the partners shared equally in the formation of one new personality.

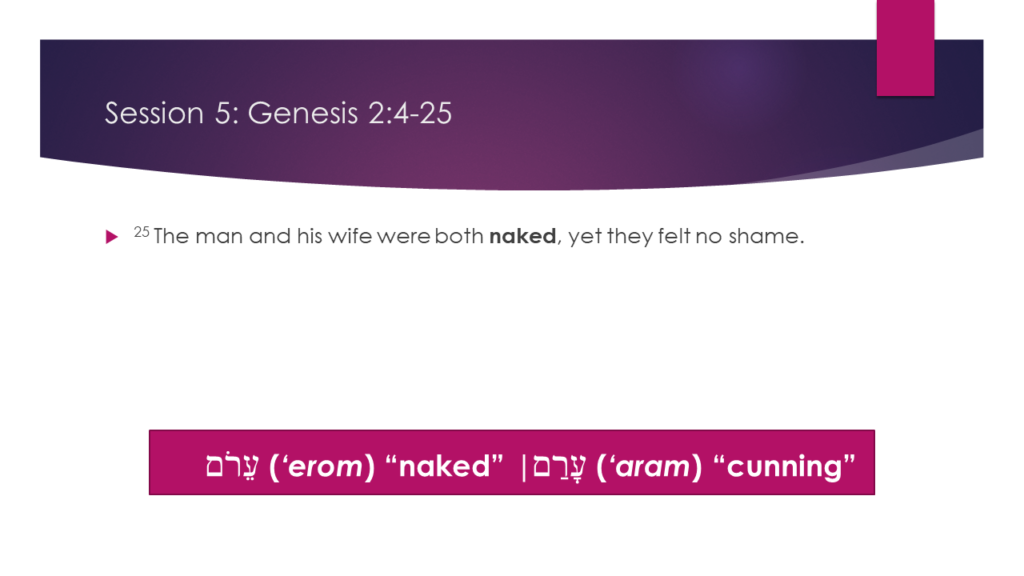

This verse sets the stage for what is to come. The word for “naked” for the man and the woman (‘erom) is written exactly the same—except for the vowel marks—as the word for “cunning” (‘aram), which we’ll see used for the serpent in the next chapter. Even if you can’t read Hebrew, you can clearly see that the three Hebrew letters are the same for both words, only the vowel dots are different.

The lack of shame is not to be interpreted as “shameless,” but as innocence. For the Yahwist, shame is not the natural condition of humankind, but it comes as a result of the misuse of our faculties. This kind of shame-fee innocence is a condition to which all humans long to return.

Conclusion:

In this section, we have seen the Yahwist holding chaos—represented by the desert wasteland—at bay and bringing plants, animals, and humans into the lush garden of creation, not just to enjoy it, but also to work with God in the maintenance of its richness and beauty. At the conclusion, we see chaos vanquished and humanity living in harmony with nature, with one another, and with God. Next time, we’ll watch as chaos returns to rejoin the battle for supremacy.