First Lazarus, Now Me

Fifth Sunday of Lent Scripture Readings

Traditionally, today has been known as the “First Sunday of the Passion,” although I always wondered why, since none of the passion narratives is ever read on this day. Yet, some clues emerge as we meditate on today’s gospel reading. Consider the background. Jesus is across the Jordan in Galilee because, not long before that, the Temple authorities had threatened to stone him to death for claiming his unique relationship with the Father—our God. For John the Evangelist, this story marks the watershed point in the life and ministry of Jesus. Up until this moment, Jesus’s mission was to reveal to the people of Israel the true nature of the Messiah—he who was to come, bringing sight to the blind, healing to the crippled, liberty to captives and the oppressed, and the gospel of hope to the hopeless.

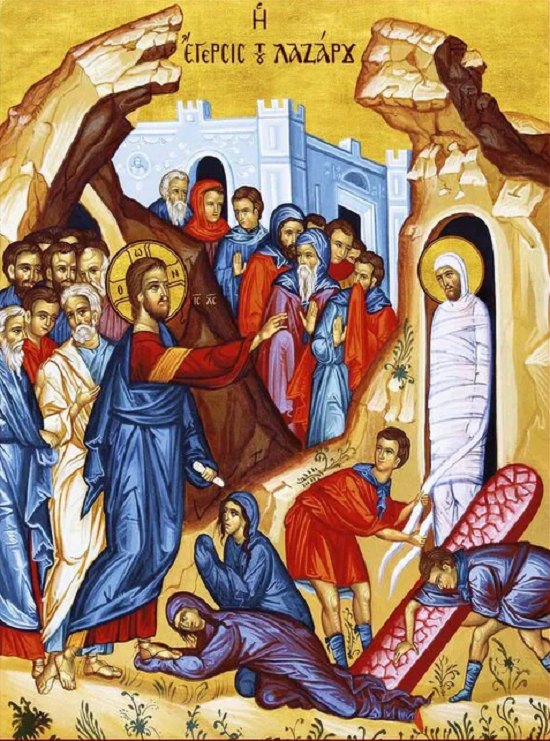

Yet, from this moment on, everything changes. Jesus sets out from here on his final journey to Jerusalem—a path that will lead him to betrayal, rejection, condemnation, suffering, and, ultimately, to execution, death, and resurrection. At this juncture, the Messiah undertakes the liberation and salvation not only of Israel but also of all humankind. In that sense, Jesus’s response to the news of the death of his friend, Lazarus, is his first step toward his passion. The way Saint John describes this event sets the stage for all that is to follow.

Did Jesus actually raise Lazarus from the dead? There’s no reason to doubt the authenticity of this event. Like the prophets Elijah and Elisha before him, Jesus was reported to have raised people from the dead in the course of his ministry. There was the daughter of Jairus and the son of the widow of Nain. All the gospel writers accepted as fact that Jesus was able to exercise power and authority even over death itself. The raising of Lazarus, although the most dramatic, was not altogether foreign to the main thrust of what was known and reported of Jesus’s actions. Did this story play out exactly as John described it? Probably not exactly. Remember that this is the Gospel of John, and John is always far more concerned with the meaning of the events than with any sort of historical accuracy.

Whom was this story written for, and what was its purpose, in addition to serving as a sort of prelude to Jesus’s last Passover in Jerusalem? Evidently, the gospel was written for the people of the first century. Look at Lazarus. In addition to being a member of a real-life family that Jesus was particularly close to, Lazarus could also be seen as a symbol of the first believers in the early Church. The relationship between Jesus and the new Christians was understood as one of great intimacy. Like with Lazarus, the trials, sufferings, and death of believers leaves Jesus greatly affected. He weeps over our ills. Yet, as the story illustrates, there is nowhere that the healing love of Christ cannot penetrate—even to the depths of the grave. There is no one so lost that the love of Christ cannot recall them to life and to wholeness. Even Lazarus’s very name speaks of that hope. Lazarus is a Latinized version of the Hebrew name, Eleazar, meaning “God is my help.”

From the beginning of the story, John presents Jesus in the role of teacher, giving his disciples the most powerful lesson possible through this prophetic action. The contrasts he presents to us are stark: darkness and light, sickness and health, life and death, sorrow and joy. The meaning of the whole passage and the event it portrays can be found in Jesus’s discourse with Martha. “I am the resurrection and the life; whoever believes in me, even if he dies, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die.” The belief in him that he’s referring to is much more than intellectual assent to an abstract idea. Merely believing that there is a God saved no one. What counts as the kind of belief Jesus is referring to is trust in God, the source and giver of life, the sustainer of life, and the One who is capable of preserving life even through the gates of death.

It is telling that, as Jesus approaches the tomb of Lazarus, he becomes “perturbed.” Was it a foreshadowing of the emotional turmoil he would be facing all too soon in the Garden of Gethsemane? What does it say about our God, and what does it say about us that the Son agonizes over us? We must never forget that Jesus taught us to see God not as an impassive, impersonal force, but as a someone—someone who suffers with us, agonizes with us, and passes with us through our death and into eternal life.

Lazarus was raised from the dead, the image of the Christian, once dead in hopelessness and futility, but now brought back to a life of faith and hope. As the Preface from the Liturgy for the Dead says, “In him who rose from the dead, our hope of resurrection dawned. The sadness of death gives way to the bright promise of immortality.” This body—our earthly dwelling-place—is fixed in time. It has an expiration date. Even Lazarus is no longer alive. But trust in God does not die, and our trust will not leave us disappointed. Our union with Christ is unbreakable. “If we have been united with him in likeness to his death, so shall we be in the likeness of his resurrection.” [Romans 6:5]

“I am the resurrection and the life,” says the Lord to us. “Do you believe this?” he asks. The extent of our belief and the extent of our trust in him will determine our answer.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.