God of Flesh and Blood

Corpus Christi Scripture Readings

As always, it helps to take a step back to appreciate today’s Scriptures better. In the first reading, the author of the Book of Deuteronomy reminds the people of Israel of how the Lord their God cared for them in their long journey from slavery into freedom. When they were hungry, God provided them with food—manna in the desert—a type of nourishing substance that reminded them of bread. When they were thirsty, God provided them with water—water that flowed from apparently solid rock. God provided the people with the basic physical necessities to sustain life. It stuck in their memories because they saw them as miracles of salvation and sustenance.

In the gospel from Saint John, the whole of Chapter 6 is dedicated to the continuation of that life-giving sustenance. It opens with the multiplication of the loaves. Just as the manna in the desert was given in response to the people’s physical hunger, so was the multiplication of the loaves. After Jesus leaves them and crosses the Sea of Galilee, the crowd follows him. Jesus criticizes them saying, “Amen, amen, I say to you, you are looking for me not because you saw signs but because you ate the loaves and were filled.” [John 6:26] At that point, instead of offering his followers bread for life, he offers them the bread of life. Just like us, the crowd resisted being shaken out of their desire for physical satisfaction, ignoring the greater gifts of the spiritual plane. In fact, their physical wants were all that they could focus on.

They challenged him to show them a sign that he could satisfy their hunger. They said to him, “What sign can you do that we may see and believe in you? What can you do? Our ancestors ate manna in the desert, as it is written, ‘He gave them bread from heaven to eat.’” In other words, they pointed out the miracle Moses performed for them and demanded to see what other miracle Jesus was going to perform to win their allegiance. In response, Jesus said to them, in effect, it wasn’t Moses who provided them with the sustenance to preserve their lives, but it was God. The answer to their hunger was on the spiritual plane, not the physical, and they were foolish to be looking for some magic trick on Jesus’s part to justify their faith in him.

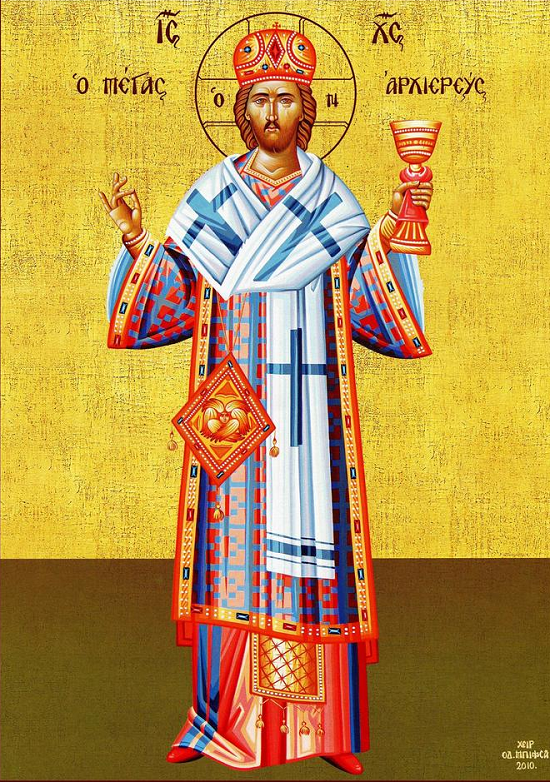

Making the leap from the physical to the spiritual, the seen to the unseen can be a real challenge. This chapter from John’s gospel ends with many of Jesus’s disciples abandoning him because they couldn’t accept his statements about his flesh and blood being the food necessary for eternal life. Just as they couldn’t imagine a spiritual dimension to Jesus’s physical existence, so even today people reject the concept that there can be a spiritual dimension to the physical and they reduce the Eucharist to merely a symbolic representation. As we can clearly see from the reaction of his disciples, when Jesus spoke about his body and his blood, he wasn’t using just a metaphor.

You’re probably already aware that there’s no institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper in John’s gospel. Instead, the whole of Chapter 6 constitutes John’s presentation of the Eucharist. As often happens, John’s narration has adjusted the historical timeline to make his point and to bring the deeper, more mystical meanings out from the events he’s describing.

There’s no doubt that the Christian Eucharist is at the forefront of John’s mind as he composes this chapter. Evidently, the words of institution that Jesus spoke—“This is my body” and “This is the cup of my blood”—are already seared into the Christian consciousness and have already become part of the Christian DNA by the time John wrote his gospel. These words were not only reported by the Synoptic gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—they were also repeated in the early Christian celebrations of the Eucharist that began almost immediately after the coming of the Holy Spirit. The words of institution are unquestionably the exact words Jesus spoke, unlike most of the other sayings of Jesus, which were recalled from memory and edited and redacted by the gospel writers. Because of the familiarity of the Christian community with these words, John felt no need to repeat them. Instead, he used this chapter to force the early Christians and their potential converts to confront the harder, deeper significance of the Eucharist.

For John, Jesus’s intention is to shake his audience out of their fixation with the physical world by insisting that they need to eat his flesh and drink his blood if they wanted truly to live. Their refusal to raise their minds and hearts from the physical to the spiritual plane demonstrates a tragic characteristic of all human beings. We need to keep God out of the world, so much so that we are continually building emotional walls between the two. Belief in God is acceptable so long as God stays in heaven and out of our everyday lives. That’s what’s behind the supposed contradiction between faith and science. People have fought wars to keep the flesh and the spirit from becoming involved with one another. Humanity is allergic to the Incarnation.

What all the Christian sacraments accomplish is bringing home the understanding that not only are the physical and the spiritual dimensions of reality not incompatible or mutually exclusive but that the spiritual dimension permeates the physical so that the two are inseparable. As creatures of the physical universe, we have no direct and unmediated contact with the purely spiritual—if indeed such a thing even exists. After all, even the resurrected Jesus had a physical dimension. Not only is the physical world not evil in itself, but it’s also in fact our only access to the spiritual dimension. The spiritual—the sacred—isn’t apart from the so-called “profane,” but exists within and through it. All that separates the sacred from the profane is our perspective. The eyes of faith can’t help but see the presence of God in all things. Nothing but moral evil can hide the spiritual from the eyes of faith.

Union with the presence of God within creation means union with the eternal Word that brought all that is into existence. Union with the Christ is union with God the Father. Our union with Jesus is life and the preservation of life into eternity. Our sacramental union with Jesus is nourishment of that living identity that we are. It’s fitting that he has given us a physical manifestation of his life-affirming presence in the bread and wine of the Eucharist. The Eucharist is far more than a mere symbol of our communion with Christ and with one another. It’s the medium through which divinity joins with humanity—the spiritual with the physical—to nourish and sustain the living connection between the two.

For centuries, scholars have described the mystery of the Eucharist as transubstantiation, meaning that the substance of the bread and wine is transformed into the substance of the body and blood of Christ. But the reality goes far beyond that. In the Eucharist, the physical and the spiritual become one. We are also transubstantiated. The substance of our mortal, physical lives is transformed into the substance of the spiritual, eternal life of the risen Christ. For he has told us, “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him on the last day.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.