Gather Us In

Sixteenth Sunday Scripture Readings

Today, let’s talk about evil. It seems to be all around us. History is replete with examples of evil run amok. We see instances of evil everywhere—people rich and poor, powerless and powerful—furthering the cause of man’s inhumanity to man. We have plenty of examples of individuals and groups taking inhumanity to ever-greater extremes—extremes of ferocity and extremes of scope. We think that none can rival the barbarism of Hitler and the Nazis, yet theirs was simply a matter of degree, not kind. It seems to me that cultures are adept at recognizing inhumanity, so long as it’s done by someone else. Seldom do cultures—including our own—acknowledge the inhumanity in themselves.

One of the principal reasons we humans have such difficulty identifying evil is that we’ve been misinformed about its nature. We don’t really understand what evil is. Even our language has been infected with false notions. We speak of “good” and “evil” as though they were things. The philosophers speculated about “good” and “evil.” The moralists lectured about “good” and “evil.” Even the sacred writings of almost all faiths—including our own—talk about “good” and “evil.” Therefore, somehow, we’ve managed to objectify and even personify evil. We’ve endowed it with seeming independence: “Deliver us from evil.”

The objectification of evil stands behind the single most pervasive reason that people use to deny the existence of God. They say, “If God exists, why is there evil?” and “If God is all-powerful, why doesn’t he just do away with evil?” The answer to these questions is as simple as it is profound. If there were no evil, there could be no good. In fact, without good and evil, nothing could exist. That’s because good and evil aren’t things in themselves but are properties of existing things. The concept of goodness expresses the value of a being. God created everything good. To the extent that anything exists, it has value—it has goodness. The Supreme Being that encompasses all things is the supreme good. There’s an ancient Latin saying that expresses this: ens et bonum convertuntur, in other words, being and goodness are interchangeable.

What, then, can we say about evil? If goodness is a property of being, then evil is not a thing at all, but a property of no-thing. It’s the result of something missing—especially something that should be there. Here’s a poem that expresses it perfectly:

For want of a nail, the shoe was lost.

For want of a shoe, the horse was lost.

For want of a horse, the rider was lost.

For want of a rider, the message was lost.

For want of a message, the battle was lost.

For want of a battle, the kingdom was lost.

All for the want of a nail.

Since evil is no-thing, it doesn’t exist and thus has no power of its own. Whatever power evil exerts is borrowed. It’s like the suction in a vacuum or the force of water going down a drain. Therefore, it makes no sense to “fight” evil. We don’t need to resist evil. That’s an exercise in futility. Our role in this life is to create. God made humankind in his own image…that is the image of the Creator. We’ve been put here to be co-creators with God. We overcome the power of evil by striving to grow our world. The world that we create is a reflection of our own being, our own goodness, our own love. If evil has any power of its own, it’s the power to instill fear in us. Jesus taught us to overcome fear by faith in the God who loves us, by hope in the power of God that he’s put at our disposal, and by love that puts that power to work in our lives and our world.

How is that reflected in today’s gospel? Once again, Matthew presents us with a parable of the Reign of God. Jesus uses these parables to invite his disciples to think and to deepen their understanding of their relationship with God. Once again, Matthew has turned Jesus’s parable into an allegory that he used to strengthen and console the early Christian Church as it faced ever-new difficulties. Once again, I want to focus on the parable rather than on the allegory.

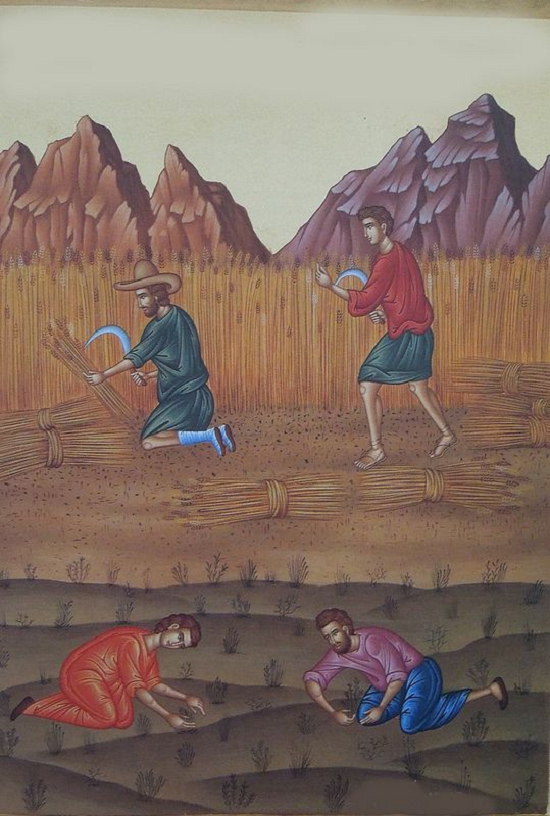

Jesus uses the image of wheat to illustrate the Reign of God. He likens it to food that sustains and nourishes life. It’s an expression of the loving-kindness of our Heavenly Father. God’s love not only brought creation—and therefore, human life—into existence, but that love maintains it and causes it to flourish. Yet, in among the wheat are found weeds. They are identified as a particular kind of weed called darnel. Darnel is a plant that closely resembles wheat, only, if you tried to cook with it, it would sicken rather than nourish you. Why doesn’t the householder—that is, God—destroy the darnel? That’s because you can’t tell the difference between the wheat and the darnel until it’s borne fruit. That’s when the darnel can be collected and discarded, while the wheat can be gathered in to be used.

That’s the way it is with good and evil. Since all things are good to the extent that God has created them, it’s hard to tell the real good from what’s lacking in goodness. Lies, for example, are hard to recognize because all lies contain partial truths. So, everything that is evil is partially good. The parable tells us to be patient. It tells us to wait and to observe. Sooner or later, what’s false will be exposed, collected, and disposed of. Sooner or later, what’s good and true will be seen for what it is and will be gathered up for the benefit of all.

As Jesus showed us in his own life, when we live in acceptance, loving surrender to the Father, and gratitude—that is, Eucharist—we overcome evil with good and produce a fruitful harvest. In fact, the evil that we see around us is, in a sense, none of our concern. We don’t overcome it by confronting it so much as by aligning ourselves with the Reign of God—that is, God’s will. What is God’s will? That we should love the Lord our God with all our heart, and with all our soul, and with all our mind, and with all our strength; and that we should love our neighbor as ourselves [Cf. Mark 12:30-31]. Gather us in, Lord. Make of us a fruitful harvest.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.