Where’s God?

Nineteenth Sunday Scripture Readings

Where is God? It seems as though everyone in today’s Scripture readings is looking for him. Elijah, Paul, and Jesus’s disciples. And they’re not the only ones. One thing that they all have in common is that God is not where they expect to find him.

I absolutely love the passage that we read from the First Book of Kings. Elijah climbs the mountain called Horeb in the Kingdom of Israel and called Sinai in the Kingdom of Judah. Either way, it’s called the mountain of the Lord. It’s where Moses first encountered Yahweh face-to-face. Elijah beds down in a cave on the mountain and waits for Yahweh to appear. He experiences a great whirlwind, and a great earthquake, and a great fire, but Yahweh’s not there. What this passage is telling us is that Yahweh isn’t like Zeus or Jupiter with bolts of lightning, or like Thor or Ba’al, gods of the storm. No. Yahweh comes to Elijah and to us in stillness and quiet where we can intuit the whispers of the universe and the murmurs of the heart.

Paul thought he’d been chosen and appointed by God to be the great enforcer of the Law of Moses. He wasn’t only an Israelite—a chosen man from a chosen people—but he was a Pharisee. He was convinced that he was on a mission from God to enforce orthodoxy. He was sure that he was acting as an instrument of the will of God. But, like Elijah, Paul discovered that God wasn’t who he thought he was and didn’t manifest himself in the ways he expected. At his conversion, nothing changed for Paul but his experience of who God is. For him, the God of love, manifested in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, broke out from the mold imposed upon him by the stipulations of the Torah. And, once Paul began to experience the radical freedom of the children of God, he could look back with longing upon the people for whom he’d spent his life in service. He saw them all too willingly bound by the shackles of the Law in service of a God who would not be bound. He experienced a kind of survivor’s guilt: why me and not them? The God that Paul discovered was not at all how he expected to find him.

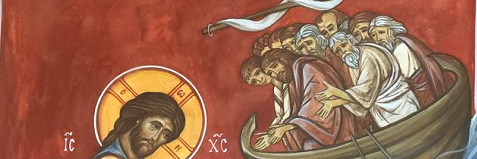

The gospel today is yet another story of discovery. As often happens, the historical event behind the gospel story eludes us. If it were, indeed, an actual happening, it’s highly probable that it was one of Jesus’s appearances after the resurrection. Also, once again, as often is the case, the historical event is far less important than the reason why Matthew included it in his gospel. The symbolism is evident. The disciples are certainly Jesus’s followers, gathered together in that boat. We could honestly say that Jesus’s followers were all in the same boat—they shared the same fate. The boat, then, is clearly the early Church caught in the storms of misunderstanding, sectarian violence, political turmoil, and religious persecution that characterized the first centuries after Christ. It may seem to us, when all is collapsing around us, that God is not there—that God just isn’t concerned.

In the midst of turmoil, the Lord approaches unperturbed. It’s interesting that Matthew, when he borrowed the story from Mark’s gospel, removed the passage that said that Jesus calmed the waves. For Matthew, God, in the person of Jesus, brings hope and comfort, but doesn’t fix everything and make things easier. Instead, he brings spiritual strength and courage to the disciples. Then, there’s Peter. There can be no doubt that Peter is the paradigm of the leaders of Christ’s Church. In fact, leadership always entails walking out into the storm unprotected. Leadership involves far greater risk than mere membership. Any leader will attest to that. The important message given here is that, in the Christian Community, leadership can only survive through an unshakable trust in the Lord. It also reminds the Church that, even when human failings prevail, the hand of the Lord is always there to lift them up again.

The understanding that we can take away from today’s readings involves our giving up and leaving behind our inadequate notions about God. It doesn’t matter what we’ve been taught by our parents or by religion or catechism classes. No retreats or seminars or brilliant preaching—even my own—can convey who God is. God is never where we think he is. As Elijah and Paul and the disciples on the sea discovered, God cannot be captured and held by our presuppositions. God comes in quiet; he comes in radical freedom; he comes amidst turmoil and fear. God comes, not to fulfill our expectations, or even to rescue us, but to challenge, strengthen, and console us.

We don’t worship a stop-gap god who’s here to fix whatever’s broken. We don’t worship a god who works miracles to reverse the laws of nature or heal human weaknesses. God doesn’t calm storms. God doesn’t extinguish fires. God doesn’t halt pandemics. God doesn’t reverse climate change. God doesn’t put a stop to wars. God doesn’t counteract inhumanity. God doesn’t put an end to cruelty, suffering, and death. These things aren’t of God’s doing. Birth and death and everything in between are woven into the fabric of creation itself. God isn’t where we expect him to be, or even want him to be.

The God that we worship brings miracles of grace. God strengthens us when we’re weak. God reassures us when we’re alone and fearful. God calms us when we’re perturbed. God consoles us when we grieve. God upholds us when we’re sick and suffering. God nourishes us with himself when we’re spiritually hungry and shares his life with us—a life that will never end.

We are the disciples in that boat being tossed about. We are Paul, grieving over the loss of those who are in despair. We are Elijah on Horeb, waiting to see the Lord. And there is, indeed, a still, small voice whispering in us, right now. Listen. It’s saying, “I love you.” And that is the greatest miracle of all.

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.