The Incarnation Paradox

Christmas Night Scripture Readings

Christmas Day Scripture Readings

Life is a paradox. The mystery of life is only revealed in death. That was a lesson I learned when my parents died. We can’t fully know who someone is until we know who they were. Likewise, during our waking hours, we struggle and strive to achieve our goals, but our success depends upon what happens when we sleep. Exercise requires rest, our appetite for food requires fasting, and breathing in requires breathing out.

As an example, there’s a new exhibit at the Palm Springs Art Museum featuring the work of a local sculptor, Phillip K. Smith III. Mr. Smith sculpts with light. One of his works features a large disk mounted on the wall and spot-lit. The surface of the disk is uneven. It’s not the light that reveals the topography of the disk, but the shadows. Light only exposes things to our eyes; shadows are what give them depth and dimension.

We’ve been taught that success means achievement: doing better, rising higher, going farther and faster, and digging deeper. Isn’t the most successful person the one who’s the best? Being the best usually means being better than everyone else, beating them all at their own game. Our striving for success only succeeds in bringing us face-to-face with paradox, and we humans don’t do well with paradox. We want things to be simple. When we can’t resolve the paradoxes in our lives, we try to avoid them. The great paradox is that when we attempt to avoid a paradox, we fall victim to it. When we try to power through the challenges of life, we discover our weaknesses. The harder we try to control the forces confronting us, the more chaos we produce. Just look at the results of the January insurrection, the war on Ukraine, or the takeover of Twitter.

Yet God is the source of all that is, and Christmas tells us that God himself is a paradox. Anything we can say about God, the opposite is equally true. God is all-powerful, yet God can’t change your mind. God is Creator, yet God is also Destroyer. God is everywhere and eternal, yet God works in space and time. God exists, yet God doesn’t exist…in the same way as anything else in the universe. God is extrinsic to the universe, but God is also immanent in it. We’re more comfortable keeping God out of it. When God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world. We can comfortably go on believing that we’re powerful and in control, while we imagine that God is out there watching it all happen. We’re blind to our paradox that, while holding God off at arm’s length, we’re ready to blame him when things go wrong.

From time immemorial, God has been trying to tell us that things don’t work that way. Power isn’t what we think it is. Control isn’t what we think it is. Success isn’t what we think it is. Life isn’t what we think it is, and God isn’t what we think he is. Gently, compassionately, and constantly, God communicates to us the warning that we’ve got it all wrong. God tries to show us that, the more intelligent and controlling we think we are, the more ignorant and out of control we become. God allows us to live the paradox, but we’re determined not to acknowledge it. That’s why God says to us, “…my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways” [Isaiah 55:8].

Yet, God doesn’t give up trying to reach us. God has all the patience in the world. God shows us the grand paradox through the creation and destruction of the material world, through the growth and decay of living things, and through the advances and declines of human history. That’s not enough. Our willful blindness refuses to acknowledge the paradoxical universe we inhabit. We refuse it until it becomes unavoidable for those willing to encounter it. God got our attention in the resurrection of Jesus. It was only then, that we became willing to consider the paradox that life will come through death. In that, we discovered the paradox of Emmanuel, God-with-us. Only then were we willing to entertain the thought that God, who is extrinsic to creation, might also be intrinsic in it.

That’s what we celebrate today. As the letter to the Hebrews proclaims, “In times past, God spoke in partial and various ways to our ancestors through the prophets; in these last days, he has spoken to us through the Son, whom he made heir of all things and through whom he created the universe, who is the refulgence of his glory, the very imprint of his being, and who sustains all things by his mighty word” [Hebrews 1:1]. Or, as Saint Paul writes in his letter to the Philippians, “Have among yourselves the same attitude that is also yours in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. Rather, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, coming in human likeness; and found human in appearance, he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross” [Philippians 2:5-8]. The Greek word for this mystery is κένωσις (kenosis), meaning self-emptying.

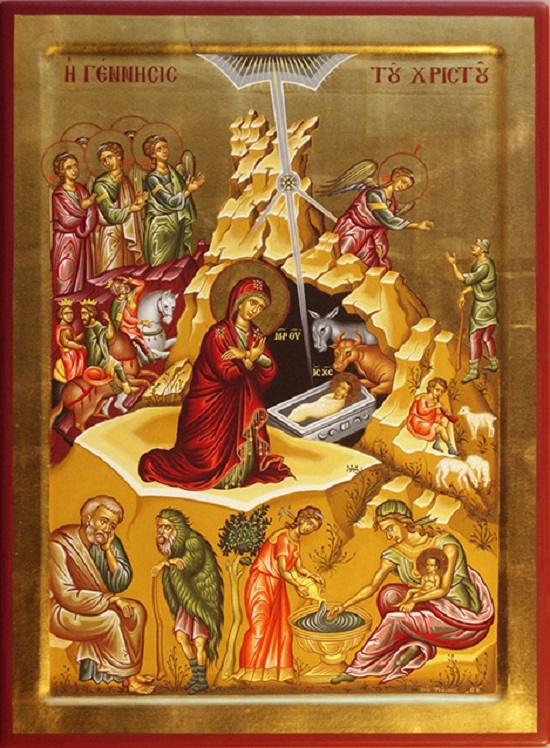

When we think of the baby in the feed trough of the cave-barn in Bethlehem, we’re invited to contemplate the paradox of who God is. The birth of the Christ child shows us how wrong our concept of God is. The fullness of God is only revealed in God’s kenosis. God’s kingdom and power and glory are only understood when we encounter God’s self-emptying. And God doesn’t communicate with humanity for his own sake. God doesn’t care to hear himself talk. What God is telling us in the baby at Bethlehem is that this is the way the universe works. This is the way life is meant to be lived. This is God’s re-definition of what “success” means.

Our Christmas joy comes from the fact that we don’t have to wait for Easter to experience the joy of encountering the divine paradox. The gospel writers understood that God’s message was there for us from the beginning. Just as God’s kingdom and power and glory come from his self-emptying, so our authority comes through acceptance; our power comes through surrender; our prestige comes through gratitude. See the paradox: God surrenders himself to our care, in the Christ child and in every person who depends upon us. See the paradox: Almighty God comes to us as helpless. See the paradox: God comes to us as bread and wine, nourishing our physical and spiritual hunger. In our joy this Christmas, we find the courage to embrace the paradox—the paradox that is God, the paradox that is creation, the paradox that is life. When we do, we’ll find that we are Mary and Joseph who bring the Christ child to birth in our world, we are the shepherds and wise men who come to adore him, and we are the angels who sing, “Glory to God in the highest!”

Readings & Homily Video (Christmas Night)

Readings & Homily Video (Christmas Day)

Get articles from H. Les Brown delivered to your email inbox.